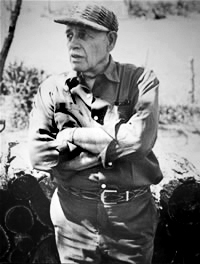

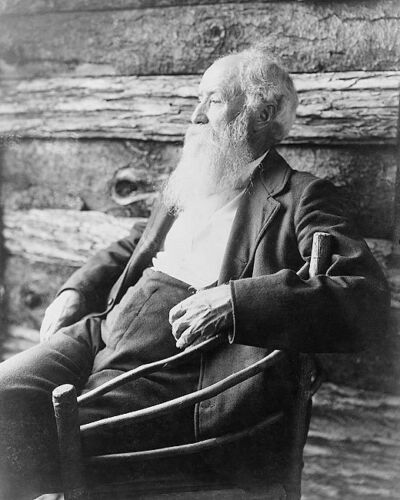

In March of 1966 Hal Borland wrote: “I didn’t plan to be a nature writer, but it has paid for the bread and dungarees when nothing else did. . .The fiction is, to me at least, wholly unpredictable. It’s an indulgence, with all the God-awful trash monopolizing the market.” Ironically, over a prolific career that spanned six decades and 36 published books, Borland would be hailed “the dean of American outdoor writers” by Publishers Weekly, and achieve his greatest success with a novel he called “nothing but a flyer on my part. I had no hopes for it.”

Harold Glen Borland was born in Sterling, Nebraska on May 14, 1900. Sterling, located on the Nemaha River in south-eastern Nebraska, had been settled only thirty years earlier, a product of the first great wave of homesteaders after the Civil War. Harold’s Grandfather was one of the town’s earliest citizens, having taken a homestead there in 1872. When Sterling incorporated in July 1876, Grandpa Borland, a blacksmith and expert wagon maker, had become a respected businessman and community leader, and was among Sterling’s first elected Board of Trustees.

Harold’s father, Will, was born in Sterling in 1878, one of sixteen children. In his early teens, Will apprenticed to The Sterling Sun newspaper, quickly reaching the level of master printer. At seventeen, Will left home to travel through eastern Nebraska and western Iowa, working for several papers and perfecting his skills. In these small country shops Will learned advanced techniques from “tramp printers,” highly skilled itinerant men who rode the freights from town to town, picking up work where they could find it. In 1896 he returned to Sterling to be with his dying father, and was at his bedside when he passed away in August. Will remained in Sterling, working as a freelance printer before taking a position as a sales advisor for a printing supply company based in Omaha. On April 26, 1899, he married eighteen-year-old Sarah Clinaberg from nearby Tecumseh, and, in 1907, became part owner and editor of The Sterling Sun, alongside the man who had first taught him the printer’s trade.

As a young boy in Sterling, Harold had what he years later described as “a kind of front row seat to. . .a way of life and a kind of living that was usual if not wholly typical of that time. The time, of course, was the beginning of the century and it just happened that the frontier was still a warm or at least a vivid memory.” He knew old trappers and farmers, Civil War veterans who had fought on both sides, had an uncle who was in the Spanish-American War. On visits to the Clinaberg’s farm in Tecumseh, Harold was thrilled to be included in berry picking excursions, learned canning and cooking skills, and helped cure beef and pork for the winter. He was especially fond of Grandma Clinaberg, an independent “pioneer matriarch” who would often tell her seven children that “every tub stands on its own bottom” and “the Lord helps those who help themselves.” Grandma Clinaberg knew when prime harvest time came in every season, and taught her children how to live with the land and make the best of all it offered.

Another local character who had a lifelong influence on Harold was “Old Phil,” an eccentric loner with wild long hair who lived in a shanty and trapped skunks and muskrats. Phil’s parents were killed when he was an infant. He was raised by Indians, trained as a scout, and served under General Custer until he was severely wounded and hospitalized only a week before the battle at Little Big Horn. Phil told exciting stories of Indian wars, grizzly bears, and massive buffalo herds that roamed the Plains not so many years earlier. To the children of Sterling Phil was a hero, “one of the last of the old scouts and frontiersmen.” From Phil, Harold learned basic survival skills and a lasting respect for nature.

In the first two decades of the twentieth century nearly a million homesteaders migrated west and settled on the Great Plains. In February 1910 a restless Will abruptly left his lucrative position at The Sterling Sun and filed a claim on the remote, short grass plains of eastern Colorado. The closest town was Brush, a full day’s wagon ride 30 miles north. The arid plains of eastern Colorado had long been considered suitable only for grazing, and, other than a few unwelcoming cattle and sheep ranchers, were largely uninhabited when Will took his claim in 1910. Harold and his father built a 14 by 20 foot shell for their home, then covered the roof and outside walls with “bricks” cut from the tough, ancient sod. With a post hole auger they drilled a well and found water where the ranchmen told them there was none. With no trees to provide fuel for the stove, Sarah burned dried cow and sheep chips. They plowed and farmed and struggled to survive on the harsh plains, often with nothing to eat but jack rabbits and corn mush. When times were desperate, Will would travel into Brush to take temporary newspaper work.

Though life on the homestead was difficult, Harold was captivated by the immense beauty of the Plains. On clear days, he would climb the haystack and strain to see the Rockies, out of view many miles to the west. He hunted for arrowheads and collected bleached buffalo bones. He marveled at the endless miles of bluestem and buffalo grass. He spent many summer afternoons watching clouds float across an “indescribable blue of sky and distance.” In spring the Plains came alive with color; teal, mallard and canvasback ducks flocked to the small, temporary ponds created by spring rains and snow melt. Harold found barely visible buffalo and Indian trails stamped into the grass years ago, and an old road made by stagecoaches traveling across the Plains. In adulthood he recalled: “It was a raw, new land, most men said; but it was raw only in terms of Midwest farming, and it wasn’t new land at all–only the white settlers there were new. We were new and I, a boy to whom the whole world was new, gloried in discovery.”

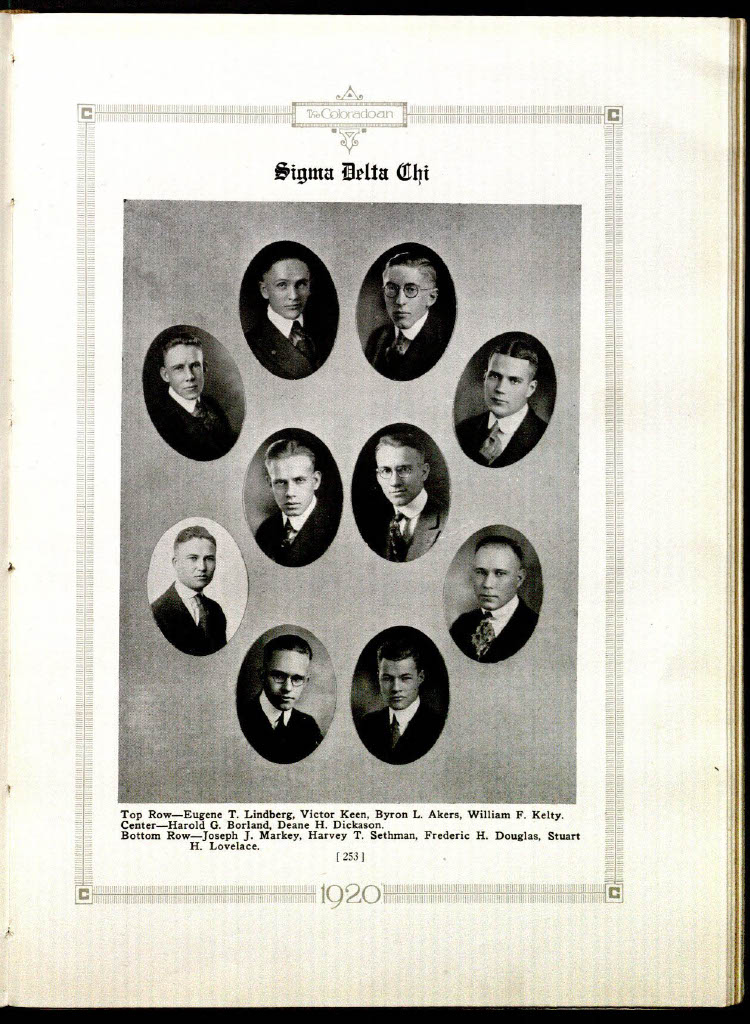

In the spring of 1914 the Borland’s left the homestead and moved north to Brush. Will took a full-time position with The Brush Tribune, paid debts and saved. In April 1915 he quit the Tribune and moved his family south to the burgeoning Plains town of Flagler, CO, where he bought the weekly paper The Flagler News. In Flagler, Harold’s own newspaper career began when he learned the printing and editing trade from his immensely talented father. During his college years at the University of Colorado and Columbia School of Journalism in New York, Harold wrote articles for The Flagler News, while also working as a correspondent for The Denver Post, The Rocky Mountain News, The Brooklyn Times and Brooklyn Standard Union, United Press, and the weekly Kings Features magazine supplement “Home Journal.” After graduation from Columbia in June of 1923, Harold shortened his name to Hal, married classmate Helen LaVene and completed his first book, then spent 1924 and much of 1925 “barnstorming” through Utah, Nevada, California, Texas and North Carolina, working as a copy reader and linotype operator, while submitting short stories and poetry to magazines. Eventually he landed a position as night editor for The Asheville Citizen, before moving back to New York and working briefly for the Ivy Lee Publicity firm. In October 1925 Borland returned to Colorado and purchased the small weekly paper The Stratton Press, only a few miles from his hometown of Flagler.

From the outset, Borland had an unwavering dedication to his work that he credited to his beloved father Will: “He gave me responsibility early, encouraged me to my own decisions, urged me to grow to the limits of my capacity.” This fierce drive to succeed was reinforced in June of 1920, when Harold and several classmates were suspended from the University of Colorado for their part in the publication of a laughably tame lampoon edition of the school newspaper, Silver and Gold. The edition had been approved by their journalism instructor, but when school officials took offense by the paper, the instructor denied any knowledge of the issue, leaving his students to shoulder the blame. Harold simply returned to Flagler without hesitation and poured his energies into his father’s paper. Borland never went back to UC, and years later reflected on UC President George Norlin’s foolish overreaction: “He expelled me from college for specious reasons at the age of 20, an act which drove the steel of resolution into my soul, to prove him wrong.”

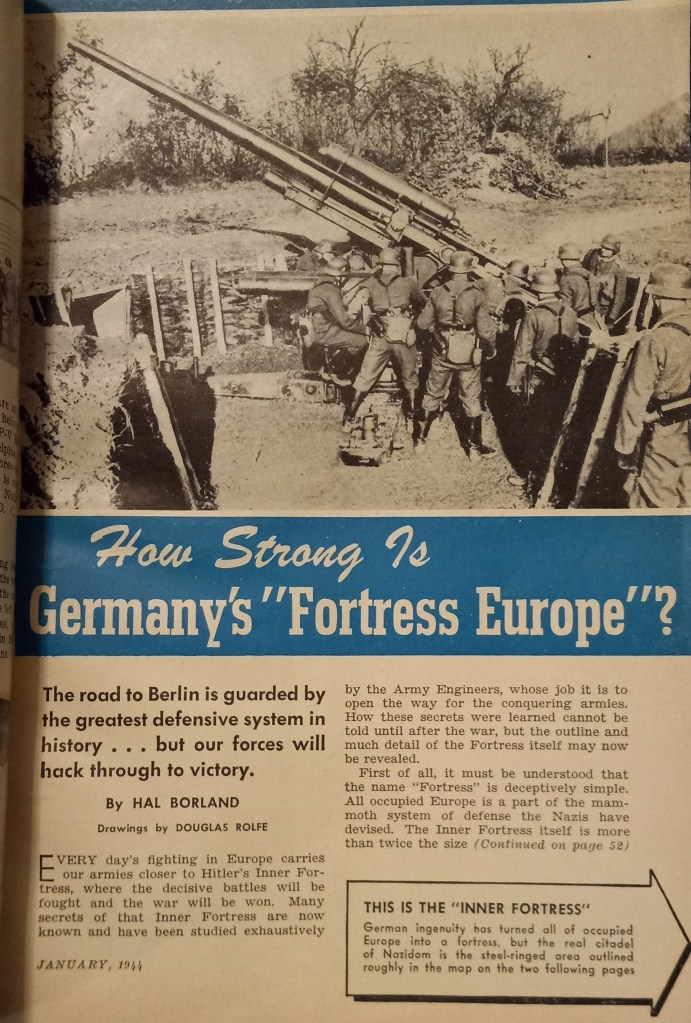

In the spring of 1926 Borland sold The Stratton Press and relocated to Helen’s hometown of Philadelphia. During the next eleven years working for Cyrus Curtis newspapers, Hal wrote over 1600 book reviews as well as several editorials a day for morning and evening editions of The Philadelphia Morning Sun and Evening Ledger. In 1937 he left the Ledger to write features for The New York Times Magazine. He stayed six years, reporting on everything from two World’s Fairs to allied war efforts during World War II. In the fall of 1941 Borland began a weekly nature column for the Sunday Times editorial page. From October 8, 1941 through February 21, 1978–the day before his death–nearly 1900 of his outdoor “editorials” appeared in the Times. In 1942 Borland published his sixth book, America is Americans, a collection of patriotic poetry inspired by Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor. During 1942 Hal also wrote scripts for the Government’s Office for Emergency Management radio program “Keep ’em Rolling,” a popular broadcast hosted by Clifton Fadiman that rallied support for troops serving overseas.

In the summer of 1943 Borland resigned the Times as a salaried employee to become a freelance writer, saying, “I left the Times because I wanted to write and they wanted to make me an executive. I left a good many jobs along the way for the same reason–that darned desk they wanted to put me behind! If they had kept me writing, I might have stayed.” He continued the Sunday nature editorials as a freelancer, scripted film documentaries on Navajo Indians, nature and geology, and wrote book reviews, short stories and features for Harper’s Magazine, The Saturday Evening Post, This Week, Holiday, Better Homes and Gardens, The Saturday Review and Readers Digest. Borland’s feature assignments would often take him on extended research journeys across the U.S., including a four month, 12,000-mile trip in the late summer and fall of 1945 for his post war report on America, “Sweet Land of Liberty.” During this trip, Hal and his second wife, writer Barbara Dodge, were married in Denver.

Hal and Barbara soon began collaborating on short fiction and novellas for McCall’s, Redbook and Colliers. The Borland’s used a tape recorder to capture their ideas, then each would work independently developing story lines. Whenever they bogged down on a piece, they would use a stream of consciousness technique over dinner, rapidly throwing out plot lines then choosing whichever seemed best. Hal took pride in never missing a deadline and stuck to a rigid schedule: “I get up between four and five in the morning and do practically all my reading then. For seven days a week, we’re at our typewriters by seven and keep at it until one o’clock or so.” By 1955 Borland had published over 350 articles and stories, both his own and those written with Barbara.

Borland was a frequent contributor to Audubon magazine, and collaborated on several books with Audubon editor Les Line. From October 1957 until his death in 1978, Borland wrote a 2500 word quarterly “reflective essay on the seasons as they come” for Morris Rubin’s magazine The Progressive. During this period, he also wrote the Wednesday “Our Berkshires” column for the Pittsfield, Massachusetts newspaper The Berkshire Eagle, and a weekly column for The Pittsburgh Press. The articles were primarily nature related, but also included politics, conservation issues, personal anecdotes, and critical pieces on Northeast Utilities and insecticides. Borland was a man of strong opinions who frequently used his columns to voice them. Borland was also a prolific letter writer, turning out hundreds of letters, typed and single spaced, and often three or four pages in length. And, in addition to his published books, Borland completed several more that never made it to print. An impressive amount of work, accomplished by simply making good use of his time.

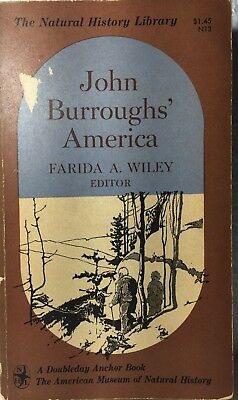

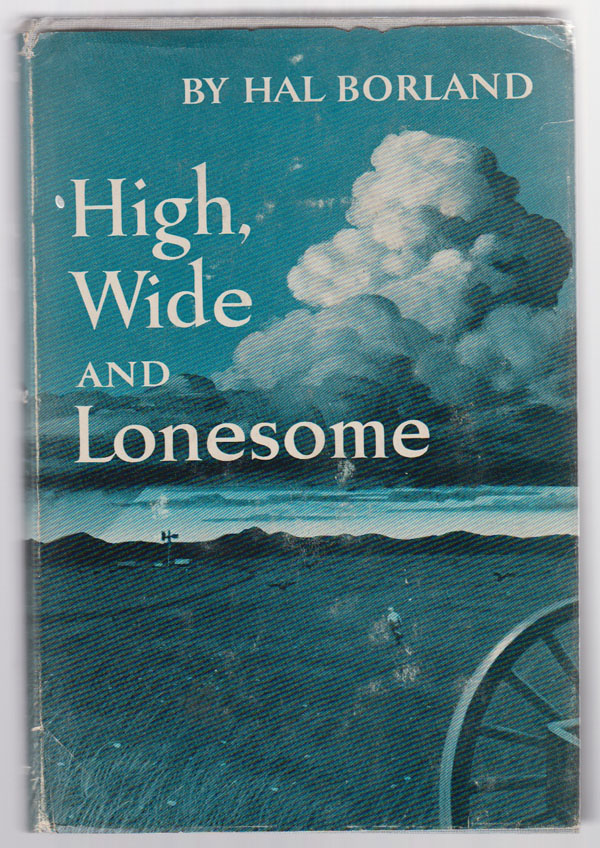

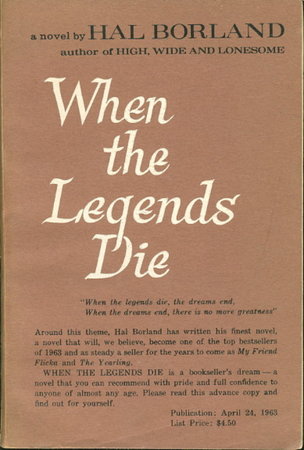

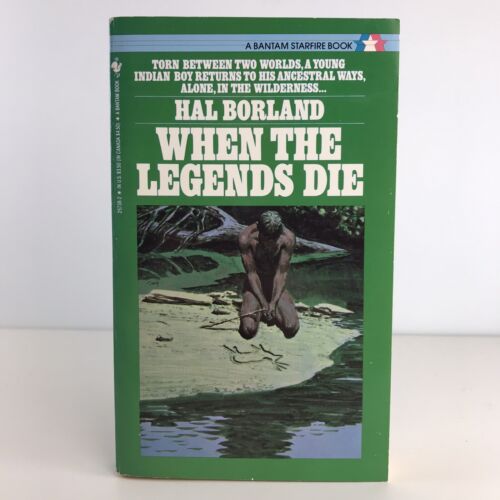

By the late 1950’s the magazine fiction market had cooled, and Hal decided to devote more time to writing books. In his Connecticut study Borland purposely sat with his back to the window to avoid distraction, saying, “The only way I know to get books written is to sit down at the typewriter and write, not wait for inspiration, whatever that is, and not spend the day staring out the window.” Between the publication of his superb Colorado homestead memoir High, Wide and Lonesome in 1956, and his death, Borland completed 29 books. By far, the most successful of these is his novel When the Legends Die, published by J.B. Lippincott Company on April 24, 1963. When the Legends Die is the beautifully written story of Thomas Black Bull, a Ute Indian boy born on the southern Colorado Reservation at Ignacio in 1907. When Thomas is three, he moves with his parents to Pagosa Springs where his father takes a job in the sawmill to pay a debt. When his father kills a man who repeatedly robbed him, the family flees to the mountains where they build a lodge and live in the old Indian ways. Thomas befriends a young grizzly bear cub and takes the name Bear’s Brother and is happy. But after a few years, Bear’s Brother is taken from the hills and sent back to the Reservation. He is again given the name Thomas Black Bull and forced to learn the white man’s ways. Thomas grows up to become a vicious bronco rider, all the while struggling to reclaim the happiness and peace he had as a child living in the mountains in the old ways of his Ute ancestors. As Hal described the book; “Tom is an Indian brought up by his mother in the ancient tribal ways. Suddenly he is plunged into the white man’s world. It’s like propelling a prehistoric man into the 20th century, and he finds that he can’t make the giant adjustment. To me, this is the tragedy of a man who grew up in the kindly, benevolent world of nature and suddenly found himself confronted by violence and brutality. How will he react? That’s how the story grew.”

In March of 1960 Borland completed the manuscript for his book The Dog Who Came to Stay and began planning for his next project. He had recently been offered a contract to write a nature book for Alfred A Knopf, and also had in mind a prequel to High, Wide and Lonesome, to be set in Nebraska in 1908, titled Country Editor’s Boy. Borland envisioned Country Editor’s Boy as the story of one childhood year in Sterling, with tales of his grandparents, friends and neighbors, “and through it will run the story of Old Phil.” While going through scrapbooks that spring, he rediscovered a short story he had written in 1938 called “The Years Are Round as the Aspens.” The story, which was set in Pagosa Springs and followed a Ute Indian boy who grows up to become a bronco rider, only to return to the hills in the end, was published in American Magazine in September 1939 with the title “Song of a Man.” When writing the story, Hal had drawn upon his own boyhood experiences in Pagosa Springs, where his father had taken a temporary editing job in 1911. That summer, eleven-year-old Harold and his father fished “in the swift white waters of the upper San Juan River” and the pristine water of Lost Lake. Harold hiked in the mountains, where he befriended old miners and loggers as well as local Ute Indians, eagerly absorbing their tales of the “old” way of life, listening to their tribal chants and learning bits of Ute language. After his graduation and marriage in June of 1923, Borland returned to the mountains of Pagosa Springs with Helen, where they camped while he completed writing his first book, a collection of thirty Native American myths and legends titled Rocky Mountain Tipi Tales. Hal made plans to someday build a cabin there, but that sadly never happened.

As Borland reread “Song of a Man” in 1960, he thought he might like to add new characters and rewrite the story as a full-length novel. In August he met with Lynn Carrick, his editor at Lippincott. Carrick very much liked The Dog Who Came to Stay (Borland’s fourth book with Lippincott) and asked Hal what he planned to do next. Hal told Carrick about his idea for the High, Wide and Lonesome prequel, and briefly mentioned an idea for a “book about an Indian boy, a bear cub and a rodeo background, the theme being a man’s inheritance.” Hal and Lynn had become good friends over the past four years and had an excellent working relationship. Borland was not fond of writing outlines; he would simply tell Lynn what he had in mind and Lippincott would draw up the contract. Carrick said he wanted to publish both books, and they agreed to go for the prequel first.

Three weeks before his meeting with Carrick, Borland had accepted the offer from Knopf for one book. It was not uncommon for Borland to be under contract with two publishers at the same time. He considered his “nature books” as separate from his fiction and autobiographical work, and preferred to have them published by a different company. Simon and Schuster had been Hal’s nature publisher, but he was unhappy with their indifferent promotion of his books. When the offer came from Knopf he “was ripe for a change” and signed the contract. Borland worked simultaneously on the Knopf book and Country Editor’s Boy for Lippincott for the remainder of 1960 and into March of 1961. He made steady progress on the Knopf book (Beyond Your Doorstep), but struggled with Country Editor’s Boy and set it aside. Hal concentrated his efforts on Beyond Your Doorstep and delivered his completed manuscript to Knopf in late spring. He then went back to Country Editor’s Boy, again with no luck, and on June 3 notified Carrick he was going to try the “Indian book” instead. Lynn readily agreed to the scheduling change and sent Borland the contract for the book, tentatively titled “The Indian,” in late June 1961 with a deadline of one year. On July 26, Hal sat down and easily wrote chapter one exactly as it would appear in the published book. (Note: When Country Editor’s Boy was eventually published in 1970, it was as a sequel to High, Wide and Lonesome, not a prequel).

In late August Lynn Carrick was relocated to London and George Stevens, a Vice-President at Lippincott, became Hal’s editor. Borland told George that “The Indian” was progressing ahead of schedule, and they decided to move the deadline up to early 1962 with publication in the fall. The project was soon sidelined, however, when Barbara’s aged mother in Waterbury, Connecticut suffered a heart attack at the same time Hal’s mother in Nebraska fell and broke her hip. Trips between Waterbury and Nebraska took up all of November and December, and it was not until January 1962 when Hal returned to work in earnest. In early January he quickly wrote the short children’s book The Youngest Shepherd, then started back full time on “The Indian.” By the 21st of January, progress on the book had stalled, and a determined Borland wrote George a “conscious letter,” where he said, “I have been pushing at The Indian because of my pride in meeting deadlines. . . .I know you told me there was no pressure from you. I appreciate that. I have generated my own pressure; and now I am going to stop pressing and finish the book in its own time.”

For the next six and a half months, seven days a week, he worked on the book, revising some sections as many as six times before he was satisfied. The character “Mary Redmond” gave Borland a great deal of difficulty and had to be rewritten over a dozen times. On August 2 Borland was optimistic the book was nearly complete and sent a progress report to George. He wrote, “This draft is finished. . . .and I hope and pray that it is substantially final. Barbara will read it next week, and I will read it through, and we will pool reactions. . . .You know the varied feelings one gets when a script is apparently done and yet may have holes, the feeling of hope and wonder and mixed satisfaction.”

To his disappointment, Hal and Barbara readily agreed the final section was weak, so he began revising again. On September 17, Borland completed his rewrite and mailed the manuscript to Lippincott, one of the few instances he delivered a piece after its deadline had passed. George enthusiastically read the work, declared it “stunning,” and congratulated Borland on a “distinguished and most interesting job. You have brought off your central character magnificently. . . .and the narrative is handled expertly.” He offered a few minor changes and suggested it be titled When the Legends Die, from an unpublished Borland poem being used as the epigraph. Borland made the revisions, and on October 27, 1962, mailed the final manuscript to Lippincott.

Throughout these hectic months Borland never missed a single Times editorial or Progressive or “Our Berkshires” column, a testament to his years as a newspaperman in Philadelphia and New York. For his October 31 Berkshire Eagle column–four days after completing When the Legends Die–Hal wrote a scathing piece titled “The Sad Case of John Steinbeck.” It had recently been announced that Steinbeck would be the recipient of the 1962 Nobel Prize for Literature, an award Borland clearly felt Steinbeck did not deserve. In the article Borland railed, “for the life of me I can’t understand this award,” and called the awards committee “incredibly stupid” for choosing Steinbeck over more deserving authors such as Robert Frost. He went on to call Steinbeck’s The Winter of Our Discontent “one of the most haphazard and unimportant novels he ever wrote. . . .almost a travesty on the serious novel and one that went to pieces in the end, as though Steinbeck got tired of what he was doing and just slapped things to any kind of conclusion.” Borland pegged The Grapes of Wrath “a period piece. . . .a good novel, but it dealt with a passing situation and actually lacked any profound statement on the condition of man. Read it now and you wonder what all the shooting was about.” He complimented Steinbeck on Of Mice and Men, saying it was “one of the best pieces of sustained writing he ever did,” but concluded “its importance is debatable.” He called Cannery Row “an uneven book of slight importance either as literature or social comment,” and tagged The Wayward Bus “a pretentious piece of trash that made even his friends wonder what had happened to Steinbeck.” Borland dismissed East of Eden, saying “his writing was diffuse and uneven, his viewpoint uncertain,” and declared Travels with Charley “full of cliches both of words and thoughts, a hack job done for magazine publication and put between covers as a book.” Borland referenced an interview that Steinbeck had recently given to The New York Times, where Steinbeck himself said he did not feel he deserved the award. Borland summed up Steinbeck’s work by saying, “there are two or three better than average novels and there are maybe half a dozen excellent short stories,” but concluded “there is no real, coherent body of Steinbeck work. . . .as a social commentator he has been inconsistent, and as a writer he has turned out some miserable prose as well as some vivid, meaningful words.”

Meanwhile, George Stevens was thrilled with When the Legends Die and was wasting no time getting it into print. Stevens had been instrumental in Lippincott’s publishing of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird in 1960, and promised to give Borland the same intense promotion they had given Lee and her masterpiece. In late December Lippincott sent Borland page proofs of the book, which he read immediately and mailed back on the 31st. Hal also sent an emotional letter to George, where he beautifully recalled an experience he and Barbara had at Mesa Verde National Park several years earlier. Hal was there to give a speech to a woman’s club, and one evening a group of teenaged Navajo boys put on a fireside demonstration of ancient chants. Hal wrote, “They chanted, and the songs had the mystery, the wonder, the sadness and exultation of that old country. . . .The feeling was deep and primary, elemental. The audience was rapt, silent; then several of the women began to cry.” When the demonstration was over, “It was several minutes before the audience roused and left the hillside, in twos and threes and in silence.” Hal recalled how he and Barbara gathered pinon nuts the next day, which gave them a feeling of kinship with the ancient Native American custom. These events are the basis for Borland’s dedication in When the Legends Die, which reads; “For Barbara, Who has gathered pinon nuts and heard the old songs in the firelight.” Hal reflected on Legends, saying, “Who knows when a book really takes root, or where, or from what seed. . . .I came out with the feeling that I came fairly close to where I wanted to, and I suppose that’s something.”

The January 1963 Lippincott Spring Catalog listed When the Legends Die with an April 24 release date. Four hundred and fifty paperbound review copies were sent to selected booksellers and reviewers throughout the country and the response was immediate. Advance orders quickly reached 14,000, and Legends went into a second printing two months before its scheduled publication date. Borland was about to have the first bona fide smash of his career when tragedy struck. On March 13, 1963, his oldest son, Hal Jr., died suddenly from a massive heart attack in Oswego, New York. He was only 38. Hal and Barbara traveled to Oswego where they spent the next several days burying his son. This was the second child Borland had lost. His youngest son Neil had passed away at age sixteen on December 31, 1945.

Borland was badly shaken and did the only thing he really could do, which was to return to work. He turned in his weekly columns, contemplated his next project, and anxiously awaited the publication of When the Legends Die. But not even his recent loss could dampen Hal’s excitement. He wrote George; “Right now I feel a little like Tom letting himself down into the saddle on a bronc in the chute, waiting for the gate to open on pub day. It looks as though we’re going to put on a show, and I don’t see how the bronc can fail to live up to his billing. It could be quite a ride.” In early April, Borland made a rare trip from his northwestern Connecticut farm into New York City for promotional interviews, and by mid-month Legends was in its third printing with advance orders over 25,000.

When Legends was released on the 24th, its reception far exceeded Lippincott’s expectations. Reviews were overwhelmingly positive, with Borland universally praised for his writing style and sympathetic treatment of his characters. Saturday Review called the book “. . .a warm, human story told with effective simplicity.” The Wall Street Journal said When the Legends Die was “. . .good reading on many counts; a book of beauty and lofty spirit, warmly recommended.” The New York Herald Tribune complimented Borland on a “. . .tremendously moving story. . .Hal Borland tells the story simply, with the authority of a master.” The Hartford Courant Magazine offered perhaps the most gratifying praise: “Hal Borland. as always, writes with an intimacy of the west and its people and his empathy for the Utes is reflected in every page. . . .For the first time in my memory, the Indian becomes a credible human creature with resourcefulness, tenderness and considerable nobility.” Sales of When the Legends Die were strong from the start, and Borland soon found himself on best seller lists across the country.

When the Legends Die turned up on many lists in 1963, though not all gave Borland cause for celebration. The American Booksellers Association chose When the Legends Die as one of eleven books of fiction given to the White House Family Library that year, and included it in their selection of 105 books “that will be given to the chiefs of state of 100 countries.” Also on the list was Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, Carson McCullers’ Clock Without Hands, and Travels with Charley and The Winter of Our Discontent by John Steinbeck. (“I rather like the company there, with only a few exceptions, which I shall not list”). When the Legends Die was considered for the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1963 but did not win. (The award went to William Faulkner for The Reivers). Over the next few years, Borland occasionally expressed his frustration with the volatile political forces influencing award committee’s decisions in the early 1960’s. In a May 10, 1964 letter to George Stevens he wrote: “I’d rather not talk about the Pulitzer Prizes. I still burn at the obvious search for special pleading or for authors whose chief distinction is the color of their skin. I had thought those were awards for literary merit, not for propaganda or topical yawps.” On March 20, 1966, Borland wrote a heartfelt letter to his close friend, naturalist Peter Farb, revealing his disappointment still ran deep: “I seem to grow more self critical. . . .You just do what you can, the best you can, and sometimes you hit it right. . . .Legends took off and still is doing well, with unexpected rewards still coming. It even had a toe-hold on the Pulitzer, but didn’t make it because Tom Black Bull was red instead of black in a year when, I have been told, color was a vital factor. How the hell would I know ahead of time? In any case, he had to be what he was. Maybe some of the boys can write for the big money, but some of us can’t, too, because we have to live with ourselves.”

His bitterness over the Pulitzer notwithstanding, Borland never needed to doubt what he had accomplished with his book, or the impact it would have on his readers. When the Legends Die quickly became a mainstay on junior high and high school required reading lists across the country and remains so to this day. The book was, not surprisingly, enthusiastically embraced by the Native American community. For the remainder of his life, Borland regularly received gracious letters from young students, many Native American, who were deeply moved by the book. Letters were often addressed to “Thomas Black Bull,” and told of the profound impact the story had on them. Hal personally answered every letter, often including words of advice and encouragement for the student’s future studies. The letters continued to arrive even after Borland had passed away. In March of 1978 Barbara received a package of letters from a ninth grade English teacher at a reservation school in Wellpinit, WA. He told of how difficult it had been for him to interest his students in basic English until they read When the Legends Die. All of them identified with young Tom Black Bull, and honestly expressed their feelings in their letters to Borland. One youngster wrote, “Myself, I would have up and left into the mountains and found my Bear Brother and gone where no one could find me. Tom, why did you let them push you around and tell you to do this and that? I could not stand to be pushed around or told what to eat, how to dress, and all those things. I feel kind of sorry for you, but you may teach your children the old ways one of these days.”

Borland occasionally gave lectures to English classes, where he cautioned students on the futility of over-analyzing his, or any, book, which only leads to finding false meanings. When writing Legends, Borland aimed for “a kind of semi-poetic job. . .maybe with overtones of meaning,” but was careful that any symbolism”not be labored.” After one lecture in 1966, Hal wrote George Stevens, “Part of my job, of course, was setting them straight on this symbolism thing, which teachers and critics dream up, and also telling them that detailed analysis of writing is a bootless exercise–it’s like taking a watch apart to find the tick; all you get is a lot of little wheels, and no tick.”

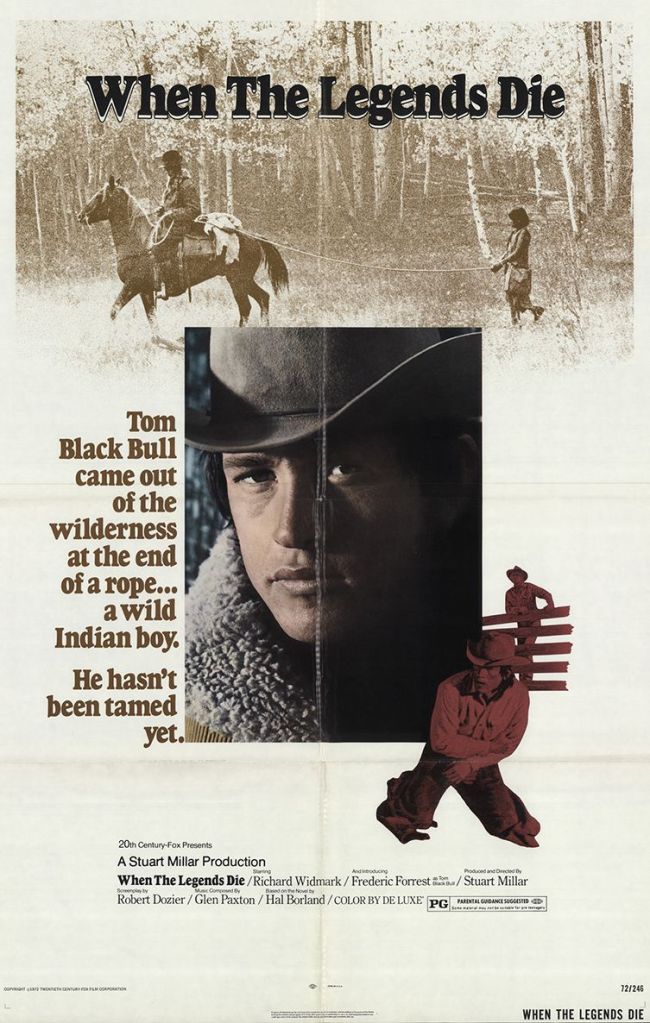

In 1966 Borland sold the film and television rights to When the Legend Die to Hollywood producer Stuart Millar and Embassy Pictures for $30,000. Millar was determined to direct the film himself and offered Borland a screenwriting position, which he turned down. Over the next five years, Millar declined several opportunities to produce the film with established directors. His persistence paid off in 1971 when 20th Century Fox agreed to finance the film with Millar producing and directing. Veteran screen actor Richard Widmark was cast in a leading role as the character Red Dillon. Widmark traveled from his home in Roxbury, CT to Borland’s farm in Salisbury, where they spent an August afternoon discussing the book. Filming was done in September and October 1971 in Durango, Colorado, and the Ute Reservation in Ignacio, the exact site Borland wrote about in the novel. The adult Thomas Black Bull was played by newcomer Frederick Forrest in his first starring role. For the role of Bear’s Brother, Millar cast a young Ute Indian boy named Tilman Box. In early December, Millar sent Borland a group of stills and Borland was completely taken by Tilman Box. Hal immediately wrote to the young actor: “I almost called you Bear’s Brother, because I just saw the picture of you in the Southern Ute Drum. In those two pictures, the ones with the bear, you clearly are the boy I was writing about. . . .I can’t think of a better choice for that role than you are. . . .you have already. . . .made my boy come true. Thank you.”

When the Legends Die has been published in the U.S., Britain, Canada, Germany, Italy, France, Spain, Norway, Japan, Holland, Portugal, Australia, Switzerland and Sweden. It has been featured in book clubs around the world. Millions of specially bound editions have been shipped to junior high and high school English classes since the 1960’s. But exactly how many millions of copies Legends has sold seems to be anyone’s guess. J.B. Lippincott Co. was purchased by Harper and Row in the late 1970’s, and Lippincott sales records have apparently vanished in company mergers and computer system changes over the years. However, Legends went through at least thirteen hardcover printings, and Lippincott was delivering new printings as late as the spring of 1975. The first Bantam Books paperback edition appeared in the late summer of 1964. By November 1972 paperback sales had passed 800,000. Bantam, Bantam Pathfinder and Starfire, and Laurel Leaf paperbacks remained in continuous printings until January of 2012. A 2001 Publishers Weekly list of All Time Bestselling Children’s Books (Volume 248, Issue 51, 12/17/2001) ranked When the Legends Die at #46, and put paperback sales from 1984 to 2001 at 3,353,965. Bantam paperback sales info from 1972 to 1984, and 2001 to 2012, appears to be lost or inaccessible. In November 2011, Open Road Media (openroadmedia.com) began offering electronic editions of When the Legends Die, as well as Borland’s High, Wide and Lonesome, and The Dog Who Came to Stay. Open Road has since added Beyond Your Doorstep, Country Editor’s Boy, Penny and This Hill, This Valley to their Borland titles. In late 2019, Echo Point Books & Media issued new hardcover and paperback editions of When the Legends Die, The Dog Who Came to Stay, Book of Days, Twelve Moons of the Year, Sundial of the Seasons and High, Wide and Lonesome. Though accurate sales figures are elusive, one thing is certain: since its publication in April of 1963, When the Legends Die has never been out of print.

In When the Legends Die, the young boy Bear’s Brother is tricked into leaving the mountains by Blue Elk, an elderly Ute who betrays his people to the reservation for money. Blue Elk tracks Bear’s Brother deep in the mountains by summoning distant memories of when he was young and lived in the mountains in the old ways. He tells the boy that he must come back to Ignacio to sing the old songs to his people, and tell them of the old ways so they would never forget. At the reservation, Bear’s Brother quickly realizes he has been lied to and that he will not tell of the old ways, but will be forced by the white men to learn the new ways instead. Borland described the dilemma as “the story of an American Indian who is stripped of his heritage and traditions, loses his identity with his own self, becomes a man obsessed with violence, and eventually returns to the peace and understanding of his own background.” In August of 1968, Borland received a letter from Dr. Robert Bergman, a psychiatric consultant for the Navajo Division of Indian Health in Arizona. Bergman talked of how he used When the Legends Die in a training course for staff members in Native American boarding schools. The participants in the course, many of Ute ancestry, were all former reservation students themselves and were brought to tears by the book, which reminded them of their own childhood experiences. A grateful Borland wrote Bergman that his letter was “tremendously satisfying” and “pleases me more than I can say,” and added, “Your report about the reception of my novel, When the Legends Die, among the Indian people and those working closely with them makes me feel very proud. I somehow feel that at last Tom Black Bull has been able to tell some of the old tales and sing some of the old songs to his own people, to help make them understand and take pride in their unique heritage.”

Copyright 2014. Kevin Godburn. All Rights Reserved.