In 1890 a thirty-one-year-old Massachusetts landscape architect named Charles Eliot recognized the need for an organization to protect and maintain natural locations throughout his home state. Eliot founded The Trustees of Public Reservations* (the nation’s first land trust) the following year to “preserve, for public use and enjoyment, properties of exceptional scenic, historic, and ecological value throughout Massachusetts.” The Trustees, a nonprofit, charitable corporation that relies on private donations, memberships and occasional public grants, obtains land through gift or purchase and currently owns, manages and protects 122 reservations covering more than 27,000 acres.

*(The group shortened their name to The Trustees of Reservations in 1954).

Bartholomew’s Cobble, a 357-acre reserve located in the village of Ashley Falls (town of Sheffield) in the southwest corner of Massachusetts, less than one mile north of the Connecticut border, was acquired by the Trustees in 1946 when the Garden Club of America, and “conservation-minded individuals,” donated funds to purchase 44 acres from then-owner George Bartholomew. The Cobble grew to its current expanse through subsequent donations and purchases of land, including the December 1969 purchase (for $67,500) of 115 acres known as Hurlburt’s Hill, one of the Cobble’s most popular attractions with its magnificent views of the Berkshires and Upper Housatonic River Valley.

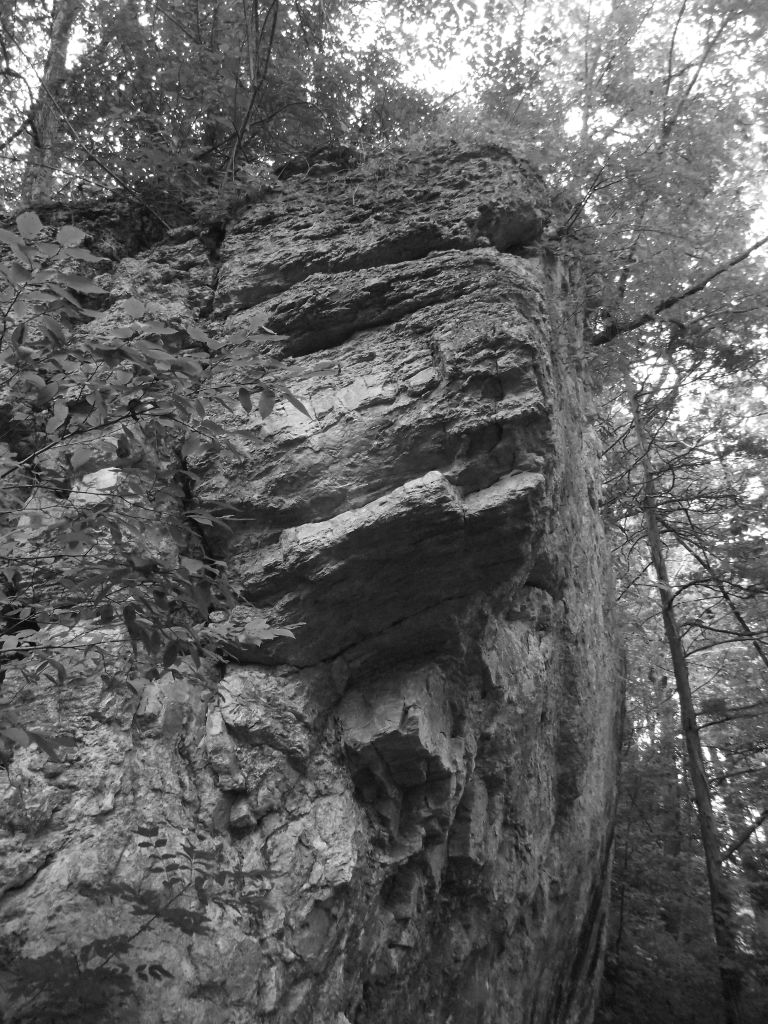

The Cobble is centered by two massive limestone knolls–the north and south cobbles–and bordered by the Housatonic River, woodlands and open meadows. The bedrock of the Cobble is composed of quartzite (metamorphosed sandstone), and marble (metamorphosed limestone), formed by heat and pressure while buried under other rock far below the earth’s surface, and “foldings” of the earth’s crust. (This transformation from limestone to marble “involves a recrystallization of the material and not a change in composition;” it is chemically still limestone). Some four to five-hundred million years ago the Taconic Mountains were formed by a folding, the “Taconic Disturbance.” Another folding, the “Appalachian Revolution,” occurred about 200 million years ago and the Appalachians were formed. Millions of years of erosion, as well as the geologically recent scraping from retreating ice, have worn away the deep rock that once covered the region, giving the Upper Housatonic River Valley and surrounding Berkshires their present, elegantly rounded, beautifully quiet shape.

The marble of the Cobble contains the mineral tremolite, making it more resilient to the effects of erosion, causing the Cobble to “rise” above the surrounding fields and river. The fertile soil of the Cobble supports a diverse collection of ferns, grasses, wildflowers and trees; more than 800 plant species have been identified and catalogued. The Cobble is also a favored nesting stop for more than 250 bird species. Botanists, geologists and ornithologists the world over have traveled to study the unique array of life at the Cobble, and, in 1971, the U.S. Department of the Interior/National Park Service named the Cobble a National Natural Landmark. But perhaps the most enduring legacy of Bartholomew’s Cobble is the peace found by those who regularly walk its trails, marvel at the majesty of the Berkshires from the summit of Hurlburt’s Hill, and silently contemplate the slow-moving Housatonic River. For many, the Cobble is a fundamental element in their life, a necessary stop in their daily routine. The Cobble repays this loyalty with unexpected wonder and surprise. During early August of 2021, the Cobble was visited by a young Roseate Spoonbill, a Florida wading bird that had never been observed in Berkshire County before. Birders from Vermont, New Hampshire, Maine and Boston made daily trips to Ashley Falls, hoping for a sighting of the historic visitor. The Spoonbill, which may have been lured north by an unusually rainy and humid summer, made itself at home among a group of Egrets, spending a week feeding in the flooded farmland before disappearing for home. (A terrific cover story on Spoonbills in the winter 2022 issue of Audubon magazine cites climate change and more than a century of ill-advised government policies as the causes for this unprecedented behavior. Spoonbills feed in shallow, fresh water. As sea levels continue to rise, salt water intrudes farther inland and Spoonbills’ nesting grounds are gradually shifting north).

In a beautiful stretch, the Housatonic River winds peacefully through the fields of the Cobble, serving as a landing strip for the hundreds of geese that fly in every day at dusk. You hear them honking in the distance, heading for home. Soon the sky is full of V-shaped formations, flying in from all directions like squadrons of B-17 bombers returning to base in the World War II film Twelve O’Clock High. You can almost picture Gregory Peck standing on the riverbank, anxiously searching the sky and counting returning airplanes. The geese circle the river in a perfectly choreographed dance. There are so many of them you expect them to collide in a tangled heap, but they never do. They sweep in, circle a couple of times, then, with their webbed landing gear extended, glide over the water to a graceful landing. Soon the river is full of geese; there does not seem to be any room for more, yet they keep arriving. Somehow, they all touch down beautifully without a single mishap.

On nights when the moon is full or nearly full, you can look across the fields of the Cobble, the trees clearly visible and casting shadows as if it was just before dusk. The Berkshires to the north and Canaan Mountain to the south are in plain view. Even without the moon the stars cast enough light to safely find your way on foot. Jets bound to and from New York and Windsor Locks carve tic-tac-toe boards in the sky with their flashing lights. Airplanes seem to fly at lower altitudes at night for some reason. On humid summer nights the orange moon-rise is more than I can even describe. Mist rises from the fields and builds into drifting banks of fog. I have stood at the edge of the fields and watched a wandering wall of fog move eerily toward me until I was surrounded, damp from the dew and shivering and loving every second of it. Only once, though, have I seen a meteor–wouldn’t mind seeing a few more of those.

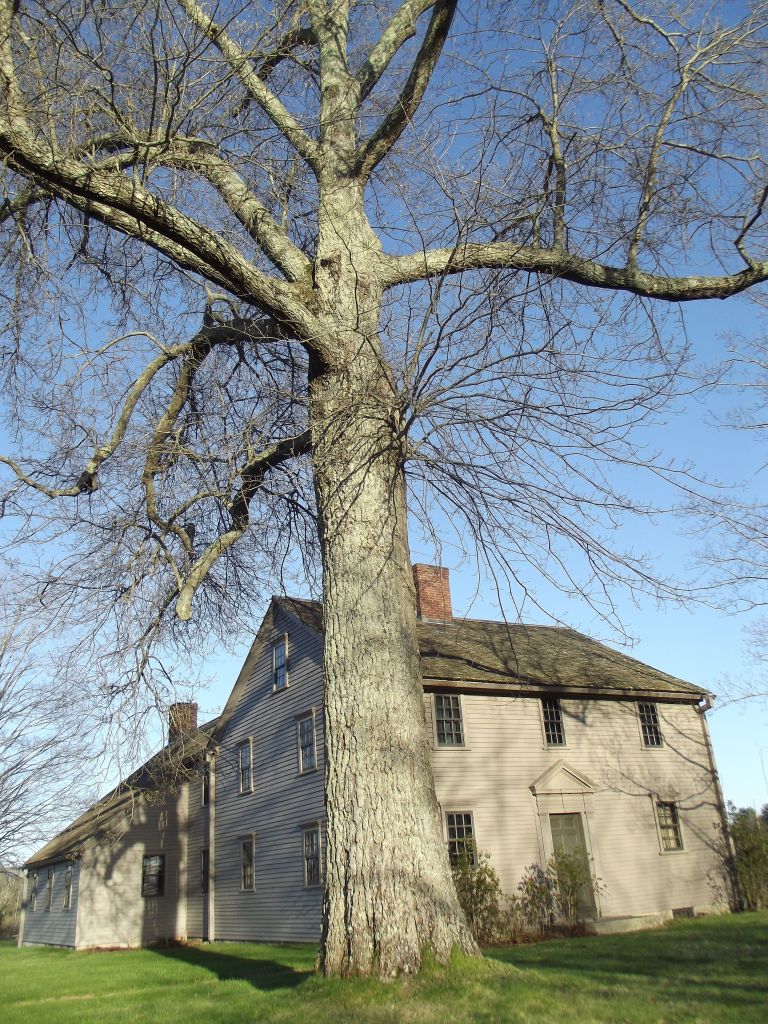

On April 25, 1724, Captain John Ashley was one of four Englishmen that “purchased” an immense tract of land in southwestern Massachusetts, more than ten miles wide and extending twenty miles north from the present day Connecticut border, from native Mohican tribes for “460 pounds in money, 3 barrels of cider and 30 quarts of rum.” The town of Sheffield, in the southwestern corner of that tract, incorporated on June 22, 1733, the first town in Berkshire County to do so. Ashley’s son, an attorney also named John, settled in Sheffield in 1732. Ashley rose to the rank of Colonel and led an attachment in the French and Indian War, served as a judge and selectman, and played a dominant role in expanding settlement and industry in Sheffield. The village of Ashley Falls is named for Colonel John Ashley.

Colonel Ashley married Hannah Hogeboom from Claverack, New York, and, in 1735, built their home along the west bank of the Housatonic River near present day Rannopo Road. The Ashley House served as a hub of 18th-century political discussion and activity in Sheffield. In January of 1773, Ashley and a committee of citizens drafted “The Sheffield Declaration” in the Ashley House, a series of resolves proclaiming “that mankind in a state of nature are equal, free, and independent of each other,” and asserting their independence from British rule. The Sheffield Declaration was published in February, preceding The Declaration of Independence by more than three years.

A family friend described Colonel Ashley as a kind and gentle man, but wrote of Hannah as “a shrew untamable” and “the most despotic of mistresses.” Despite his belief in individual freedom, Colonel Ashley was the largest slave owner in Sheffield. “Mum Bett,” one of Ashley’s five adult slaves, was born in the early 1740s and had been a slave in the Hogeboom house as a child. Mum Bett fled the Ashley home in 1780 after a physical altercation with Hannah and inspired by overhearing discussions of The Sheffield Declaration and the recently enacted Massachusetts Constitution. Mum Bett walked to the home of Theodore Sedgwick, a Sheffield attorney and friend of Ashley’s, and a member of the Sheffield Declaration committee. In August of 1781, at the County Court of Common Pleas in Great Barrington, Sedgwick argued for Mum Bett’s freedom based on the Massachusetts Constitution, winning the case and setting a precedent for the abolition of slavery in Massachusetts. Mum Bett adopted the name “Elizabeth Freeman,” and passed away on December 28, 1829. Colonel Ashley died in 1802 at the age of 92.

After Colonel Ashley’s death, the vast Ashley land holdings were divided among children and grandchildren and eventually sold. The Ashley House had several private owners during the 19th and early 20th-century. Wyllis Bartholomew purchased the house in 1838 and left it to his son Hiram in 1846. Hiram then sold it to his son George in 1852. (The Bartholomew’s also began purchasing large tracts of land from the Ashley family). George A. Brewer purchased the home and 220 acres in 1882 and ran the property as the Eureka Stock Farm. Harry N. Brigham, a great-great-grandson of Colonel Ashley, purchased the house in 1930 and moved it a short distance to its present location on Cooper Hill Road. Brigham and his wife Mary added a small addition to the house as living quarters, and displayed their collections of antiques and pottery in the Ashley House. Edward Brewer and his wife purchased the house in 1945. Brewer had lived in the house as a child when it was owned by his father. The Brewer’s supplemented the Brigham collection with antique household items and farming equipment.

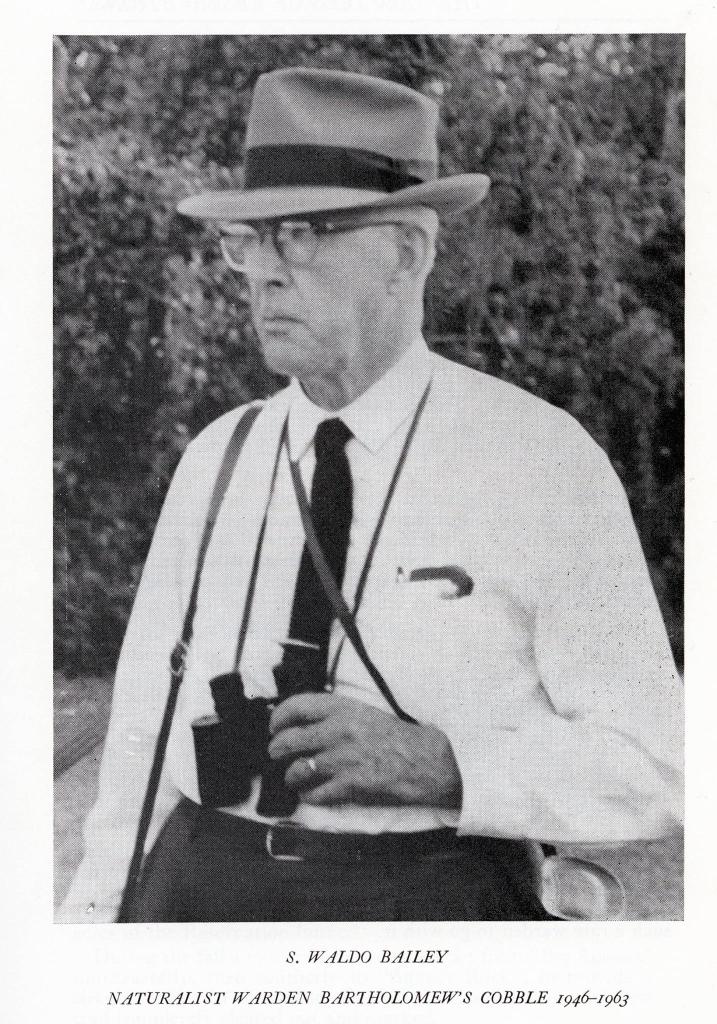

Soon after the Trustees purchased the Cobble from the Bartholomew family in 1946, Waldo Bailey was hired as the reservations’ first Warden. S. Waldo Bailey was born July 10, 1885 in West Newbury, Massachusetts. At an early age, Bailey developed a keen interest in nature and birds in particular. Using the scarce books available at the time, Bailey immersed himself in the study and observation of birds and the natural world that surrounded him. Bailey also indulged his passion for Native American folklore, hunting for arrowheads and Indian relics on his frequent field trips in Essex–and, later, Berkshire–Counties.

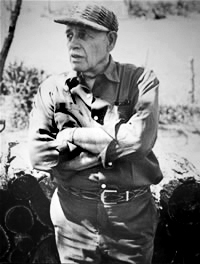

In 1902, at age 17, Bailey began documenting his discoveries in his journals. Over the next sixty years Bailey created a remarkable record, more than 4,000 pages long, of bird sightings and migrations–complete with intricate charts of monthly and annual bird counts, detailed observations on plant-life, wildflowers and weather patterns, inventories and drawings of the arrowheads and Indian artifacts that he seemed to instinctively find with little effort, travel dates and locations, as well as his endlessly engaging personal thoughts and insights on all he had seen. Bailey’s journals reveal a man deeply committed to his life’s work, a passionate observer who never faltered in his search for knowledge. Before he reached the age of thirty he had published several articles in The Auk, an ornithological magazine established in 1884. Bailey was also an exceptional photographer and early proponent of color photography in the 1920s. Bailey’s superb photographic work is second only to the awesome achievement of his journals.

Bailey moved to Pittsfield, Massachusetts in 1916, supporting his family with an unlikely position as a cost accountant for the General Electric Company, while continuing his field trips throughout Berkshire County. During the 1920s, Bailey taught a nature appreciation course at Pittsfield High School, and offered traveling lectures on nature, ornithology and photography. Bailey left GE when the Great Depression hit and spent the next several years working for the National Park Service, as well as a supervisor in the Berkshire County Civilian Conservation Corps, while continuing to publish articles, lecture and teach. Bailey was a member of many ornithological societies and committees, and served as president of the Hoffmann Bird Club, a Berkshire County group formed in 1940 and named for Ralph Hoffmann, a friend and field trip companion of Bailey’s, and the author of A Guide to the Birds of New England and Eastern New York (1904). After leaving the Park Service, Bailey was hired as Warden for the Lenox Bird and Wildflower Sanctuary (Massachusetts Audubon Society), a position he held until April of 1946.

Bailey was good friends with a Pittsfield resident named Rene Wendell. Though 31 years his junior, Wendell shared Bailey’s love of nature and enthusiasm for Native American artifacts. “R.W.” is mentioned often in Bailey’s journals as a companion on arrowhead hunting trips to favorite locations in Stockport and Schaghticoke, New York, among others. Wendell’s son, Rene Jr., served as the Cobble’s Warden from 2002 to 2015. In 2014, Rene (pronounced “Rennie”) built a cabin-style screened deck overlooking the Housatonic River. Visitors to the Cobble are invited to sit and read their favorite nature writing, record thoughts and observations in their journals, or simply have a snack and enjoy the view. The beautiful deck is one of Rene’s many outstanding accomplishments during his tenure at the Cobble.

The observations recorded in Bailey’s journals are far too numerous to try to summarize here, but two in particular merit a mention. On September 20, 1953, Bailey wrote that “A party from the American Museum of Natural History, of New York, visit the Cobble,” a group that included Miss Farida A. Wiley. See my article “Anatomy of an Award” for more on Miss Wiley and the role she would play in Hal Borland’s life in 1967 and 1968. Two days later Bailey wrote, “Astronomically Autumn enters at 4:23 A.M. Our brief Summer is over, yet the Autumn brings balmy days, and from year to year seems to loiter later than formerly. Is our season actually changing, as the rapid recession of the glaciers in the Northern Hemisphere might indicate? It’s doubtless too slow an evolvement for a single lifetime to register.”

Hal and Barbara Borland purchased their farm along the bank of the Housatonic River on Weatogue Road–two miles south of the Cobble–from Nelson Case on July 26, 1952. The Borland’s had been living on Rock Rimmon Road in Stamford, CT, making frequent trips about the country for Borland’s freelance magazine and newspaper work. But a serious illness in February of 1952 caused Borland to reevaluate his life and future. Borland wrote of the event in his 1957 book This Hill, This Valley:

“Five years ago I was taken to a hospital and partook of a miracle. I went there dying of a ruptured appendix and advanced peritonitis, and I came back alive. I went there while Winter was passing. . . .I came back to March. . . .March and I were alive, getting acquainted with each other all over again. . . .

“March passed, Spring strengthened, and I knew that I, too, had come to a new season in my life. Almost half my life had been spent in a daily job, a good part of it at a desk in a city. Because of some urgency in myself, I had lived most of those years at the edge of the country, near woods and open fields. I spent evenings and weekends there. . . .

“All that time I had made occasion, at least once a week, to renew my acquaintance with the trees and flowers, the weather and the wind. However, I felt the need to remain close to the city, never more than an hour away. The habit was deeply ingrained, and though I compromised by owning a few acres of hillside and brook and coming to know them intimately, I was being trapped by suburbanization. . . .

“Then I went to the hospital and came back, and it all seemed more of a compromise than a man should make. Reappraisal was inevitable. Barbara, who is my wife and who had known that I would come back when others doubted, agreed that there were things more important than an assignment in Maine or Tennessee. . . .So we sold our suburban acres and moved to Weatogue, to live, to write, to see and feel and understand a hillside, a river bank, a woodland and a valley pasture.

“We came here, not to a cabin in the wilderness but to a farmhouse beside a river. So far as the legalities are concerned, we bought and own a hundred acres, one whole side of a mountain and half a mile of river bank. I have spent the months and years since, living with this small fraction of the universe and trying to know its meaning–to own it, that is, in terms of observation and understanding.”

It did not take long for Borland to find his way to the Cobble and Waldo Bailey. The two became close friends, often spending afternoons sitting on the porch of the Warden’s cabin, walking the fields of the Cobble, and hunting for arrowheads. On May 28, 1958, Borland began his weekly “Our Berkshires” column for the Pittsfield, Massachusetts newspaper The Berkshire Eagle, the start of a twenty year run with the exception of a three year break between April 1968 and August of 1971. Borland’s first column featured the Housatonic River, setting a precedent for the many columns he would devote to the river, Ashley Falls, the Cobble and Waldo Bailey, including his August 6, 1958 column “The Cobble”s Waldo Bailey:”

“I don’t know how S. Waldo Bailey happened to be chosen as warden of Bartholomew’s Cobble, and I doubt if anyone really knows. But I have a theory about such natural oases and the people who shape their public character, and it fits this occasion. Any reservation is the result of the work and determination of a few people, and when it comes into being it picks its own warden by a kind of mutual process of elimination. That, regardless of the details, is how Waldo Bailey came to the Cobble. The Cobble needed him, and he needed the Cobble.

“. . . .He has lived in Berkshire County 42 years, still lives in Pittsfield. After he quit the accounting office he spent a time in the forest service. Then, 12 years ago when the Cobble was established, he became the first warden. He is the only warden the Cobble has had. He has probably been host to at least 20,000 visitors there.

“As we sat and talked the other day at the warden’s cottage, Waldo Bailey looked more like a conservative, middle-aged businessman than an outdoorsman. He wore a white shirt and tie. His hat was a gray fedora. He wore low, rubber-soled shoes. He smoked cigars. But his mind ranged back to Indian arrowheads on the boyhood farm, to the smell of salt marsh, to snowshoe trips up Greylock in 28-below-zero weather, to conservation policies and slipshod lumbering, to stream pollution, to the Cobble’s history.

“. . . .If Waldo Bailey didn’t love the Cobble he wouldn’t drive 60-odd miles every day from April till November to watch over it, cherish it, share it with 2,000 visitors every year.”

Bailey was mentioned frequently in Borland’s column, often in articles titled “Notes from the Daybook” and “Interlude at the Cobble.” In one, Borland wrote, “If I hadn’t seen the cardinal I probably wouldn’t have stopped. I was driving up the back road and slowed down at Bartholomew’s Cobble, as always, and on the ground under a cedar just beyond the entrance was this cock cardinal. He looked at me with an expression almost like Waldo Bailey’s and practically said, ‘Hello. Come on in.’ “

In his September 3, 1958 “Our Berkshires” column, Borland became the first to advocate for the purchase of the Ashley House from then-owner Edward Brewer. Borland wrote:

“Mrs. Brewer died three years ago. Mr. Brewer is now 80 years old–he looks a spry 65, by the way–and he would like to see the old house in safe hands, properly protected for the future. For a nominal sum he would turn it over to an authorized group, preferably a state agency, complete with its furnishings, glass, pottery and other collectibles.

“The house stands on a seven-acre plot within a stone’s throw of Bartholomew’s Cobble, already a public reservation. As a private museum of regional history it attracts a constant flow of visitors. . . .and visitors must make appointments with Mr. Brewer. He is a generous host and a knowing guide, but he is not there all day or every day. After all, it is his home, not a public place.

“It should be made a public reservation, a monument to the history of western New England. The modern wing, which supplements the original house admirably, would make ideal quarters for the warden of a combined Ashley House-Bartholomew’s Cobble reservation. The house itself should be a museum. It stands on a part of the original Ashley grant, which included the Cobble.

“If I read the Ashley will correctly, most of present Ashley Falls village and its nearby area were owned by Col. Ashley at the time of his death, for he bequeathed some 3,000 acres. He was a prosperous man, a distinguished man, a leader in every sense and a maker of history. His house should become a public monument, not only to Col. John Ashley but to those who came after him and to the history of our hopes and our dreams and our highest purposes. . . .”

Though Borland was proposing the Trustees acquire the house, a group of local volunteers known as “Colonel Ashley House, Inc.,” perhaps inspired by Borland’s article, purchased the property in 1960 and opened it as a museum.

In September of 1961 Waldo Bailey published his paper-bound book Birds of Bartholomew’s Cobble, a companion to a field guide on the ecology and history of the Cobble that he had written in 1948. On April 6, 1963, Bailey suffered a fatal heart attack in a field in Schaghticoke, NY. He was 77 and died as he had lived his entire life–in nature, hunting arrowheads on the land that he loved. On May 22, 1965, Bailey’s Cobble Warden’s Cabin was opened as a museum in his honor, featuring a small sampling of his arrowhead, butterfly, insect, bird and bird nests, and photography collections. In 1995 the new, much larger, visitor center on Weatogue Road opened to the public. The center features a wrap-around deck and public restrooms, is handicapped accessible, and boasts an impressive collection of bird and animal displays, as well as several beautiful Rex Brasher bird prints. The center also has a fantastic library of vintage and classic nature books, including many Hal Borland titles. The Cobble no longer has a full-time Warden, but a Trustees agent is at the center on Saturdays and Sundays from May through September. The Bailey Museum closed to the public in 2001 due to safety concerns and the cabin’s remote location. Bailey’s artifacts were relocated to the new Visitor Center and the Trustees Western Massachusetts office in Stockbridge.

In the spring of 1970 the Trustees announced their intention to “preserve and protect the Cobble’s existing values and to add new and exciting features which will immeasurably enhance the property’s appeal as a scientific, scenic and educational area, we enlarge the present Reservation and add to it a new dimension–the oldest house in Berkshire County, constructed in 1735 by Colonel John Ashley, which overlooks the Cobble.” To this end, the “Bartholomew’s Cobble-Colonel John Ashley House Campaign” was launched on May 17, 1970 at a meeting of campaign members, held at the house. The Ashley House would serve as a museum as well as living quarters for the Cobble Warden, and could be “purchased for the amount of its mortgage, some $20,000.” The Trustees set a fundraising goal of $167,500 for the acquisition of the house and additional properties, including “Ashley Field,” a pasture adjacent to the Ashley House that one walks across to reach the Visitor Center. Berkshire Eagle columnist and long-time Cobble advocate Morgan G. Bulkeley was appointed campaign Chairman, and Hal Borland was named a Co-Chairman for the committee’s Connecticut chapter. The Beinecke Foundation offered to match the first $25,000 raised, followed soon after by a $5,000 gift from The Berkshire Eagle and $6,800 in private donations. By the end of 1970 the campaign had raised $62,000. The Trustees acquired the Ashley House from Colonel Ashley House, Inc. in 1972. On February 10, 1975, the property was added to The National Register of Historic Places.

Hal Borland continued to devote “Our Berkshires” columns to Bailey and the Cobble throughout the 1960s and 70s. His recurring “River Report” monitored progress made in cleaning the Housatonic River, which had been severely polluted by centuries of sewage disposal, chemical waste from paper mills in Pittsfield, Housatonic, Lenox and Lee, and PCB contamination from Bailey’s former employer, General Electric. Hal Borland passed away from emphysema on February 22, 1978. Borland was honored in a trail bearing his name by the Friends of Bartholomew’s Cobble and the Colonel John Ashley House at their Bartholomew’s Cobble Field Day on June 23, 1979. The location of the Borland Trail was specifically chosen for the significance it holds for Borland and the Cobble. In their June 1979 newsletter announcing the Field Day, the Friends wrote:

“In the afternoon, Morgan Bulkeley, Chairman of the Local Committee for Bartholomew’s Cobble, and Mrs. Hal Borland will dedicate the Borland Trail linking the Cobble with the Colonel John Ashley House. Preservation of the Ashley House and its reunion with the Cobble was Hal Borland’s dream, a goal successfully realized with the purchase of 35 acre Ashley Field two years ago.”

The entrance to the Borland trail lies directly across Weatogue Road from the entrance to the Cobble Visitor Center. As you walk the trail through Ashley Field–still farmed for hay today–you have a clear view before you of the lower Berkshires, just as Hal Borland and Waldo Bailey surely did on their visits in the 1950s and early 1960s. Borland wrote of his friendship with Bailey in his article “Rock Garden in a Cow Pasture,” published in the May 1975 issue of Audubon magazine:

“If I were empowered to create a wild garden to suit my whims, I think I would call into being just such a place as Bartholomew’s Cobble. You probably don’t know Bartholomew’s Cobble, which is an old cow pasture with two rugged knolls of marble, situated in the southwest corner of Massachusetts. . . .

“When I said my wild garden would be like the Cobble, I meant the original reservation that was established in 1946. . .it is the original Bartholomew’s Cobble that impressed me nearly twenty-five years ago, when we first came to northwest Connecticut, and it still does.

“S. Waldo Bailey, warden-naturalist in charge of the Cobble from the time it was established till his sudden death in 1963, catalogued 740 species of plants in the original area. Besides the ferns, he listed 493 species of wildflowers, 95 trees, shrubs and vines, 61 mushrooms, 30 lichens, and nine mosses. There probably are a number of species still to be identified, especially among the mushrooms, and the grasses have yet to be catalogued.

“Waldo Bailey practically was the Cobble when I first knew it. We had moved to the far northwest corner of Connecticut, and a neighboring farmer had mentioned ‘the Cobble.’ I asked what it was, and he said they used to picnic there when he was a boy, an old cow pasture that now was a nature reservation. So we drove up there, only a few miles, walked in, and were soon confronted by a big ruddy man in a gray fedora and a gray business suit complete with white shirt and tie. That was Waldo Bailey. When he saw that we knew a chickadee from a starling he gave us the run of the place, asking only that we be careful of the ferns. It was a dry year and the ferns had suffered.

“We became good friends. He was a Massachusetts farm-boy who became a cost accountant and worked for General Electric until the Great Depression. Then, he once told me, he was glad to get out of an office. He took a job with the U.S. Forest Service and felt free again. He left the forestry job to go to the Cobble when it was established as a reservation, and it always seemed to me that he was a part of the place–firm, stubborn as its native limestone, warmed with birdsong, and softened in unexpected places with wildflowers. Birds were his first love, and he had listed 235 species at the Cobble.

“He was a self-taught naturalist with interests that ranged from prehistory and geology to weather and photography, as well as birds and botany. He had a keen eye for Indian arrowheads, could walk across a newly plowed field and pick them up like pebbles. He and a fellow arrowhead collector were walking across a field not far from the Cobble in 1963 when Waldo Bailey died of a heart attack, simply dropped dead. . . .

“Waldo Bailey’s belief, and in a sense the philosophy behind Bartholomew’s Cobble, was put into words one afternoon when I sat with him on the porch of the warden’s cabin, since enlarged and made into a compact little nature museum and library in his honor. We were discussing the change in weather, year to year, and how plants respond. ‘It’s surprising,’ he said, ‘how most plants will live out a bad season and come back. They just pull back into themselves and wait, which isn’t a bad idea. Ferns have been doing that a long time, a good many million years.’ He stared away for a moment, then said, ‘We can learn a lot from places like this. Nature manages things pretty well, manages her own balances. Man upsets the balance time after time, but nature always tries to restore it.’ “

After Bailey’s death in April of 1963, his journals and substantial collections of books, butterflies and insects, arrowheads, artifacts and photographs were inherited by his daughter Priscilla. Priscilla lived her entire life in the Pittsfield home where she was born. Like her father, Priscilla was a great lover of nature and birds, and a long-time member of the Hoffmann Bird Club. Though family members expressed indifference to the journals, Priscilla kept the entire collection intact until she passed away in 2015 at the age of 95. In the last years of her life Priscilla had been friends with Hoffmann Bird Club member Matt Kelly. Kelly was helping Priscilla organize the collection, and had been asked to edit the journals into a much shorter book form, although he had not seen the journals until after Priscilla died. After Priscilla’s passing, ownership transferred to relatives who did not have the means or interest in preserving the collection. They kept and gave away some items, and the rest–including the seventeen binders containing the journals–were thrown into a dumpster.

Kelly was notified by a mutual friend named Sue Cook that the journals were being discarded. Kelly immediately contacted the family, and, through a series of negotiations, saved the journals with the agreement that the Hoffmann Bird Club would assume ownership and their use was strictly on a non-profit basis. Kelly showed the journals to other bird club members including Rene Wendell, and it was decided that the collection should be accessible for public use. Kelly contacted Professor Thomas Tyning at Berkshire Community College for help in making the journals available on the internet, and gave the seventeen binders to Tyning in 2018. Alex Olney, a student at the college on a work-study grant, spent four months scanning and rescanning and creating a search option for the more than four-thousand pages of Bailey’s lifetime devotion to the natural world. The binders containing Bailey’s journals are currently in the collection of the Chapin Library at Williams College in Williamstown, Massachusetts. To view the journals online, visit hoffmannbirdclub.org.

For more on Bartholomew’s Cobble and the Colonel Ashley House, or to plan your visit, go to thetrustees.org.

Copyright 2023 Kevin Godburn All Rights Reserved

Discover more from halborlandamericancountryman.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.