On the first Monday of every April, the John Burroughs Association gathers in New York City and presents their Burroughs Medal to the author of “a distinguished book of nature writing that combines scientific accuracy, firsthand fieldwork, and excellent natural history writing.” Other than perhaps a Pulitzer, no honor is more revered by the nature writer. Since the award’s inception in 1926, Rachel Carson, Edwin Way Teale, John Kieran, Loren Eiseley, and Barry Lopez, among many others, all carried home the Burroughs Medallion.

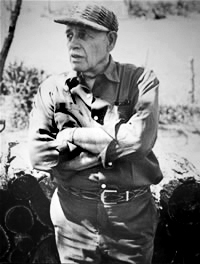

By the early 1960’s, Hal Borland had established himself as a preeminent voice in the natural sciences. With three undisputed nature classics already to his credit (An American Year, 1946; This Hill, This Valley, 1957; and Beyond Your Doorstep, 1962), Borland had long ago earned the respect and admiration of peers and fans, and had amassed a shelf-full of awards for his efforts. But the Burroughs Medal had thus far eluded him.

Borland’s journey to the Burroughs Medal would be a long one, the culmination of a campaign that began rather innocently in a letter to George Stevens, Borland’s editor and good friend at JB Lippincott Co. On April 3, 1962, Borland wrote Stevens:

“I’ve never gone in for honors, as such, but there are a couple coming up that would interest me. One is the John Burroughs Medal, and the other is one of the Columbia School of Journalism’s Alumni Awards, given annually. I don’t know what one does about such things, or whether you just sit and work and wait to be tapped. But I doubt that it’s quite proper to call. . . whoever is in charge of the Burroughs group, Richard Pough I think, and say, ‘It’s Borland’s turn.’ Anyway, maybe it ain’t Borland’s turn. Do you know about such things? Do any of your colleagues? I feel quite brash even mentioning this to you, but I would be proud of a feather for my cap, and it wouldn’t hurt the books, would it?”

And so began a six-year skirmish that would cast Borland and two of his most ardent supporters against the Burroughs Association’s indomitable Secretary-Treasurer, Miss Farida A. Wiley.

Farida Anna Wiley was born in Sidney, Ohio in 1887, the daughter of ranchers who raised percheron stallions and devoted free time to planting trees. At an early age, Farida (pronounced Fareeda) developed a keen interest in birds and nature. By age eleven she was sending reports on bird sightings and migrations to the U.S. Biological Survey in Washington. She immersed herself in the study of the natural world, a lifelong passion that would make her a self-taught authority on plants and trees, insects and ornithology.

In 1919 Farida moved to New York City to live with her older sister Bessie and brother-in-law Clyde Fisher. George Clyde Fisher was born in Sidney on May 22, 1878. Like Farida, Clyde developed an early fascination with nature, and astronomy in particular. He received his A.B. degree from Miami University in 1905, and he and Bessie were married that same year. After Fisher earned his Ph.D. in botany from Johns Hopkins University in 1913, he and Bessie relocated to New York where Clyde took a position as Associate Curator for the Department of Public Education at the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH). When Farida arrived in 1919, Fisher helped her land a part-time job teaching nature studies to blind students at AMNH, the beginning of her association with the Museum that would last until 1981.

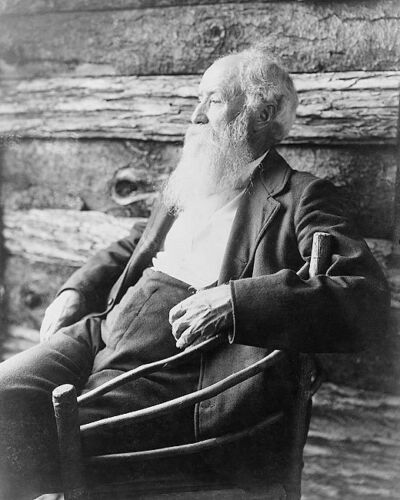

When he was a youngster in Ohio, Clyde began a correspondence with John Burroughs, and over the years the two developed a close friendship. On November 6, 1915, Clyde and Bessie made their first visit to Burroughs Riverby home on the Hudson River in West Park, NY. Clyde, an accomplished photographer, later recalled; “Knowing that Mr. Burroughs did his writing in the forenoons, we proposed not to disturb him until lunch time. . . .I had brought my camera, hoping to get one picture of the great poet-naturalist. Before noon I started out to secure a few photographs about his home. . . .While focusing my camera on the Summer House, I was discovered by Mr. Burroughs, who appeared at the door of his Study, and after cordially greeting me, said, ‘I thought you might like to have me in the picture.’ ” Clyde took three photographs of Burroughs that day: “So my wish was more than fulfilled on that first visit.” After lunch, Burroughs led his guests on a walk to his cabin retreat, Slabsides, discussing native plant and animal life along the way and recalling past visitors. As they said goodbye at the railroad station in West Park that evening, Burroughs told Clyde, “Whenever you want to come to Slabsides, the key is yours.”

Clyde and Bessie visited Burroughs and “camped in this mountain cabin, for two or three days at a time, about twice a year since that first visit.” Burroughs would typically receive guests at Slabsides in the spring and fall, but preferred to spend summers at Woodchuck Lodge, at his birthplace in Roxbury, New York in the Catskill Mountains. During a visit to Woodchuck Lodge, Clyde and Burroughs lounged in the hay barn discussing the work of Thoreau. While Burroughs spoke highly of Thoreau, he also “referred to certain peculiarities and to a number of surprising inaccuracies” in Thoreau’s writing. But Burroughs concluded, “I would rather be the author of Thoreau’s Walden than of all the books I have ever written.”

Clyde and Bessie visited Burroughs and camped at Slabsides over the weekend of November 6-8, 1920, the fifth-year anniversary of their first visit to Riverby. Also in attendance were a small group of Burroughs’ close friends, and Bessie’s sister, Farida Wiley. On Sunday the seventh, Burroughs cooked his “favorite brigand steaks” for lunch and spent the afternoon with the group, discussing his latest book, Accepting the Universe, and examining the surrounding plant life. Clyde “made what proved to be the last photographs of him at Slabsides,” and the last of the nearly two hundred photos that Fisher had taken of Burroughs since November of 1915. (Several of Clyde’s photos were published in The Life and Letters of John Burroughs, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1925). John Burroughs passed away the following spring, on March 29, 1921. Several months after his death, Farida Wiley was among the small group of friends who founded the John Burroughs Memorial Association to honor and preserve the legacy of the beloved naturalist.

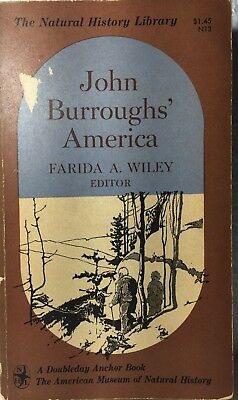

Wiley became a full-time member of the AMNH educational staff in 1923, and was named Director of Field Courses in Natural History and Honorary Associate in Natural Science Education several years later. As part of her “Natural Science for the Layman” course, Wiley conducted weekend field trips to sites in Staten Island, Westchester, Long Island, New Jersey, and National Audubon Society reserves in Connecticut. For many years Wiley also taught nature and ornithology courses at Pennsylvania State College and New York University, and from 1947 to 1967 led a summer program at the Hog Island Audubon Camp in Maine. By the early 1950’s, Wiley had been named Assistant Chairman of the AMNH Department of Public Instruction, and was an associate in the Museum’s Conservation and Ecology departments. Wiley’s first book, Ferns of Northeastern United States (1936), was for many years the definitive field guide on the subject. In the 1950’s and early 60’s, Wiley edited the Museum’s “American Naturalists” book series, collections of excerpts from naturalists including John Burroughs, Ernest Thompson Seton and Theodore Roosevelt. Farida never married–she was forever “Miss Wiley.”

In the mid 1930’s Farida began leading spring and fall migration bird walks in Central Park. Walks were held Tuesday and Thursday mornings, with two walks each day, departing at 7:00 and 9:30am. Walks were held rain or shine, and proved an immediate success. The walks often attracted seventy or more birders, many of whom were regulars who attended multiple walks each year. Farida kept a mailing list of all her birders, including descriptions of each to help remember their names. On days when birds were few, Farida simply instructed the group on the Park’s tree, plant and insect life instead. “She’s a walking encyclopedia,” said one devotee. The press took notice of Miss Wiley; Sports Illustrated and The New York Herald Tribune ran features. The New York Times described her as “bluff, wiry, freckled and partial to tweed suits.” The Washington Post wrote, “She was fond of rust-colored tweeds, sensible shoes and long-billed caps and tam-o’-shanters. She walked at a gallop, binoculars in hand. . . .She wore a pince-nez on her nose. . .her eyes were clear, fierce and alert, crackling with the spirit of scrutiny.” Farida frowned upon disturbing or removing anything from the Park: “We gather nothing in a sanctuary. We do not smoke in a sanctuary.” When asked about the seedy characters they encountered in the early morning park, Wiley replied, “We just step right over them.”

The New Yorker magazine was especially fond of Miss Wiley, running ten features on her between October 1953 and September 1977. In one article, New Yorker reporter Geoffrey T. Hellman attended a Wiley-led field trip and depicted Farida as “Our leader, a slim, erect lady with a determined chin and a brusque but feminine manner, was wearing a trim tan suit, moccasins, and steel-rimmed spectacles that in no way dulled her piercing eyes.” Hellman observed the familial atmosphere of Miss Wiley’s walks:

“The fact that I was a newcomer to what amounted to an unofficial club became apparent to me as a number of my fellow-travelers (mostly ladies wearing either plaid skirts and black woolen stockings or dungarees) greeted Miss Wiley and one another by name and fell into enthusiastic reminiscences of the fall season’s previous junkets. . . .I found myself one of a society for whom, or for many of whom, the day’s excursion was no isolated spree but part of a continuing way of life.”

On May 10, 1962–five weeks after his letter to George Stevens–Borland received notice from Columbia University that he would indeed be the recipient of a Columbia Journalism Alumni Award for 1962, in honor of his “notable accomplishments” since graduation from the University. Borland picked up the honor on May 24. The following spring, April 29, 1963, Borland was again contacted by Columbia informing him of his inclusion on the Fiftieth Anniversary Honors List of the Graduate School of Journalism. According to this letter, the Honors List “recognizes professional accomplishment by alumni of the school,” and “was chosen from names submitted by alumni-at-large and approved by vote of a committee of alumni and faculty.” Borland received his bronze medallion on May 15. What role–if any–George Stevens played in these two awards (Stevens did not attend Columbia) is unclear, but they were without question well deserved and overdue.

But inquiries made by Stevens regarding the Burroughs Medal had gone nowhere, and the matter of a Burroughs award remained stalled until early in 1967 when Les Line joined the effort. Les Line, nature photographer and essayist, was hired by Audubon magazine in 1965 as assistant editor, and appointed editor of the magazine in the fall of 1966. In June of 1964, then-editor John Vosburgh had written Borland, “I’m sure our readers would be grateful to see an occasional piece by Hal Borland in Audubon magazine.” When Line assumed leadership in 1966 he substantially increased Borland’s presence in the magazine. (Line invited Borland to be an Audubon contributing editor in October of 1967, and the two frequently collaborated until Borland’s death in 1978). In early February 1967 Line wrote to Richard Pough, founder of The Nature Conservancy and Burroughs Association board member, recommending Borland for the Burroughs Medal. Pough responded: “Thanks for your suggestion of Hal Borland. I second it strongly and am passing it on to Miss Farida A. Wiley at the American Museum of Natural History, the secretary of the John Burroughs Association.” The 1967 recipient had already been chosen (Charlton Ogburn, Jr. for The Winter Beach), and again the issue stalled until November, when Line took action and another Borland friend, naturalist Peter Farb, entered the fray. The following excerpts are from letters exchanged between Line, Wiley, Borland and Farb during November and December of 1967.

Line to Borland, 11/29/1967:

“After a lot of thought as to the best approach, I have mounted an attack on the John Burroughs Medal Committee. The key to success, the mountain to be conquered so to speak, is Miss Farida A. Wiley at the Museum of Natural History. She is Secretary, I believe, of the Burroughs Committee, and the gal who has the biggest say as to who gets the medal. And, frankly, I think she has it in for you.

“For example, in a note to Dick Pough last year she referred to you as a travelogue and camping writer. And she has been known to say ‘Borland makes mistakes.’ Possibly, but who in Hell doesn’t. And ‘mistakes’ may really be a matter of interpretation, particularly when something disagrees with the staid scientific view of nature.

“At any rate, I have written her a letter, copy enclosed, and shipped the batch of Borland products off to her post-haste.* Blind carbons of my letter have gone to Dick Pough and Roger Peterson, who is on the committee. I don’t know Miss Wiley personally, except that she does lead the frequent bird walks in Central Park. Whether we will win or lose this year, I am not about to hazard a guess. But if we go down, it will be fighting.”

*(Twelve Borland books, supplied by George Stevens).

Line to Wiley, 11/29/1967:

“It was not quite a year ago that I suggested to my good friend Dick Pough that serious consideration should be given to awarding the John Burroughs Medal to Hal Borland. . . .

“I have long felt that if any single American nature writer epitomized the spirit of John Burroughs it was Hal Borland. While I am admittedly prejudiced, I consider him our finest living nature essayist. It has been said that Hal Borland may make mistakes. Undoubtedly this has happened, but I think anyone would be hard-pressed to find any nature writer, from Burroughs to this day, who has not erred, or, perhaps, interpreted some phenomena of nature differently than some scientist.

“I was also surprised at your comment to Dick Pough last February that Borland’s books are of a travelogue and camping nature. This is hardly an accurate description of Borland’s essays, for I don’t recall that Borland has ever written a book on camping or travel.

“I’m wondering if the John Burroughs award committee might not consider Hal Borland’s newest book, Hill Country Harvest, for its 1968 award. Or, it is my understanding that the Burroughs Medal may also be given for an author’s lifework. With this in mind, I have sent to you under separate cover a selection of twelve Borland books. . . .”

Wiley to Line, 12/2/1967:

“I have your second letter recommending that the judges. . .consider Hal Borland’s last book Hill Country Harvest.

“Thank you for your interest. That book has been in the hands of the judges since the middle of September. I have nothing to do with the selection of the recipiant of the award, I only send the books that have been recommended to the judges and appraise them of the comments that the judges made about the books.

“No decission has been made for this springs award.

“I enjoyed the last article by Borland that you published where he was reporting on his childhood experiences at Thanksgiving time. But, since you bring it up, I will have to say that the article in the earlier edition of Audubon magazine where I found within two pages, 10 errors, as I remember it, I stopped reading.

“No doubt Burroughs and other of the earlier writers did make mistakes in their reportings, but unlike the writers of today, they had very few books to consult to make sure their observations were correct.

“Sorry you’re sending all those Borland books here as it is too late to send them to the judges. . . .

“You are certainly to be congratulated on the appearance of the Audubon magazine under your supervision. I don’t know where you get the superb color work done.

“Sorry not to be able to help you on the matter that seems so close to your heart.”

Borland to Line. 12/2/1967:

“Glad to get your letter of the 29th, with the enclosure. I think your approach was perfect, and somewhat heroic. The lady must be rather a formidable person, and for such a one the best line of attack always seems to be frontal and direct. You did it splendidly. . . .

“Here is an amusing one. . . .A month or so back Natural History magazine asked me to do a piece on my reference library as a possible guide for amateurs building their own reference shelves. And about 2 weeks ago the editor phoned and asked if I realized that I had mentioned 68 books in the piece. . . .Then he said they were running some kind of contest and had $500 left over, and would I mind if they used it to buy those 68 books and make a special prize of a Hal Borland Nature Library. I didn’t mind. So I guess that’s what they’re going to do. Right under Farida Wiley’s nose! Good Lord, it just occurred to me that I may have made a mistake in one of those titles!”

Line to Wiley, 12/4/1967:

“I do regret that my recent letter was the second concerning Hal Borland’s new book. . . .I profoundly apologize for inundating you with correspondence on behalf of a favorite author.

“I am really chagrined that an article with so many errors found its way into the pages of Audubon. . . .

“I would certainly appreciate it if you could take a few minutes of your valuable time to mark-up that particular article with the errors that you caught and send it to me. . . .

“Certainly, ten errors within the space of two pages would make one such as yourself decide to throw up your hands in horror.

“I hope, one day, to join you on a Central Park bird walk. But I find that an editor’s free time just doesn’t exist.”

Line to Borland, 12/5/1967:

“The reply from the formidable Miss Wiley was prompt and blunt. I enclose a copy of her rather astonishing letter and a blind copy of my carefully worded response to her.

“What I have politely told her, in reference to the alleged errors, is to ‘put up or shut up.’ This is the way I always handle chronic bitchers, and our dear Miss Wiley now has her glorious chance to prove her point.

“Frankly, I expect this falls into the same category as her ‘travel and camping’ goof. The gal obviously has it in for Borland, and I am sure I haven’t won a friend.

“I searched my correspondence, and I can find no previous letter to her about Hill Country Harvest. And I’m certain she’ll raise all sorts of hell for Natural History when she finds out about the book yarn which you wrote for them. Gadzooks.

“I understand Miss Wiley called this afternoon while I was in conference asking about the box of books and I expect she will ship them back here. Collect undoubtedly.”

Borland to Farb, 12/7/1967:

“. . . .Do you, among your acquaintances at the Museum of Natural History, know one Farida Wiley? Here’s why: Last year Dick Pough, whom I have never met face to face, nominated me for the Burroughs Medal. Farida Wiley thumbed me down. Seems she makes the decisions, runs the committee, and nobody can overrule her. Anyway, she seems to have told Pough that I wasn’t eligible, having no new book last year, and besides I was just a ‘hiking and camping writer,’ and besides that I made too many mistakes of fact. This year Pough nominated me again, with Hill Country Harvest, and was told that I hadn’t a chance, the way I get it. But someone persisted, with the help of Les Line, editor of Audubon mag, and got a set of my in-print books to submit for the award for a career award. Line got into the middle of it, though he is not on the committee, and all at once there was a white-hot feud, Wiley and Line, she calling names, he pulling no punches, and Borland out there in the middle! That seems to be where it stands right now. I’ve seen carbons of a couple of letters, hammer and tongs stuff. Beyond that, I know little except that Wiley seems determined to shoot me dead. And there is an ironic side to it in her own bailiwick. Natural History mag is going to feature that piece of mine on the books and buy all 68 of those I named and give them as a prize, ‘The Hal Borland Nature Library,’ in some contest they are running.

“As I was saying, do you know Farida Wiley? Just how long are her horns, how sharp are her claws, and who the hell is she, anyway?”

Borland to Line, 12/8/1967:

“The mails do odd things. Your carbon of your Dec. 4 letter to Wiley arrived day before yesterday, and I based my note to you on it. Now comes the letter about it, and the stat of the Wiley letter to you. . .My God, what an illiterate person she is! She ‘appraises’ the judges of their comments. And she can’t spell ‘recipient’ or ‘decision.’ Oh, boy oh boy oh boy. Well, I’m sorry you were the butt of her rancor, but sometimes we can be proud of the enemies we make. It will, I agree, be interesting to see what, if anything, she does if she finds out about that book piece in Natural History. The loss seems to be all yours, I’m sorry to see. I never had any good will from her, obviously, so I ain’t lost nothing. . . .”

Farb to Borland, 12/8/1967:

“Your letter really shocked me for many reasons–among them the rather startling fact that you had never received the Burroughs Medal. I would have felt certain that over your long career you must have received it many times, particularly since your own evocative work is what I had always thought was the very thing the Burroughs Association was supposed to encourage.

“I wish I could be more hopeful, but let me tell you anyway what I did this morning and the progress to date. It frankly doesn’t look too promising. I called John Hay and finally reached him at his retreat in Maine. John is the only Burroughs winner I know well enough to level with completely and whose judgment I also trust. John told me that the past winners are not consulted; for example, he had nothing to say about Ogburn getting it last year for Winter Beach. . . .I then tried to call Shirley Miller at Audubon who is your stoutest admirer and also, as I recall, one of Farida Wiley’s old friends. Shirley is off for a couple of months on vacation, but I am trying to find out where. I don’t know if she is still friendly with Wiley or not, but we can try. I called some friends at the American Museum and they all tell me it is pretty much of a mystery how the winner is selected; anyway, I stirred up some trouble and indignation and also got a partial list of some people on the awards committee. The only three who would be qualified to push you and who you probably know well yourself are Ed Teale, Roger Peterson, and John Kieran. I did a Reader’s Digest piece on Roger and have known him for years, but he is quite weak when it comes to things like this; anyway, I don’t know if he is back from Africa where he was squiring a bunch of biddies around for a tourist agency. Ed Teale is incommunicado on his England book. Kieran and I have only exchanged blurbs and pleasant reminiscences, but have never met. . . .

“I called Les Line and discussed it with him and he filled me in and amplified on your letter. He and I were both invited to a cocktail party at the American Museum next Wednesday and we decided to go and corner some of the people there; Farida Wiley herself might even show up. Anyway, I have the chairman of one department already lined up and Les and I are going to descend on Dean Amadon whom we both know and who is on the board of the Burroughs Assn. All this sounds like a lot of activity, but I really don’t think the flurry is going to produce much. It is one of those cases. . .where no one knows who has responsibility for what. There is obviously a vacuum which Wiley fills.

“Do you really mean you don’t know who she is? About 80 by now I guess. For years and years she has led a Saturday morning bird walk in Central Park for Museum members. The New Yorker thinks she is a terribly precious old lady and does about two columns a year on her. I recall that she may have written one original book herself, but the main thing she has produced is an awful series of excerpts from naturalists that Devin-Adair published some years ago: Theodore Roosevelt’s America and John Burroughs America and so forth. I’ve never met her, although I’ve seen her at the Museum from time to time. . . .

“I’ll let you know what happens. Worse comes to worse, Les Line and I will hold our own party for you the same night. We couldn’t think of any other book that might come close to Hill Country Harvest.“

Borland to Farb, 12/10/1967:

“Now I remember. She is the quaint bird-walk woman. I never met her, had forgotten her utterly though I did read a New Yorker piece about her once. . . Good Lord, the time you spent on that bootless errand! I do appreciate it, but it seems so useless all around. You’ve got your own work to do. No, I don’t know Peterson at all. I do know Kieran. . .But John is getting old and rather remote, in a way, and he loves to be loved. Teale, as you say, is busy. Of the other officers and directors of the Burroughs Assn., most are unknown to me. I see Rutherford Platt whom I have panned and for whom I have little respect as naturalist or author.* Otherwise, strangers. So don’t waste any more time on it. I can live without that award, have for a long time.”

*(Rutherford Platt received the Burroughs Medal in 1945 for This Green World).

Farb to Borland, 12/13/1967:

“I just returned a short time ago from the American Museum party where I had a long and frank discussion with Roger Peterson. Roger asked me not to repeat any of it to you–so here goes, with the understanding that you will not attribute it to him or me. Yes, your name has come up in the past and been voted down. There is a small select group that does the choosing, and you probably have the list of names. Farida Wiley and Dean Amadon both carry a lot of weight, but several others also have a vote–among them Rutherford Platt, whom I have also demolished in several reviews. Roger isn’t so much concerned about your reputed ‘inaccuracy’ as he is about what is considered corny titles of your books. He didn’t read Hill Country Harvest because of the title. I assured him that he was missing something. He asked me why I thought you should get it this year. I made a rather impassioned speech. I then challenged him to name another possible candidate this year who would come close to you. Anyway, he promised firmly that he would energetically support your name this year. Frankly, I don’t think he will. He looks out for himself first, and as soon as he senses trouble he runs far and fast. . . .I hope Les Line had more luck With Dean Amadon than I did. I had one of my friends at the Museum who is chairman of a department put a bug in Amadon’s ear about you and your qualifications; so when I came up to him tonight I guess he knew what I was after and he took off like a bat out of hell. He has a reputation for running from trouble.

“Anyway, that’s where it is now. If it makes you feel any better, Donald Culross Peattie was vetoed every time his name came up–and, instead, people like Archibald Rutledge were given the award ( I always regarded him as the nature faker of our times).”

Borland to Farb, 12/17/1967:

“Let’s drop it. The more I hear about the Burroughs Association, the less I want their damned medal. Just out of curiosity, I looked up Rog Peterson’s book titles. Also those of one John Burroughs. Some day when you want a bit of wry amusement, try it. Peterson certainly shows a vivid imagination in his. But, by God, he’s right. Hill Country Harvest is corny. But I’ll bet he’s the kind who doesn’t recognize a pun even when it is introduced to him by name. Anyway, as I say, drop it.”

Line to Borland, 12/22/1967:

“Farida Wiley sent me a half-dozen alleged errors found throughout our presentation of items from Hill Country Harvest. Most of them are a matter of semantics, and I’m checking a couple of others out, but I think she may have found one real slipup. From the sample she gave, I think she had to work pretty hard.

“I’ll get back to this in a few days and will keep you apprised on the correspondence. Peter Farb, as you undoubtedly know, is on our team. And I think I’ve swung Dean Amadon around to our side.”

Borland to Line, 12/27/1967:

“I would like to see Farida Wiley’s list of errors, just to see what kind of thing she takes exception to. I have no doubt there was at least one valid one in her list, maybe more. But, dammit, she can’t spell!

“Yes, Peter Farb told me about some of the things that have happened. Peter, of course, has a low boiling point and he is so much a partisan of mine that I have to discount some of his report. Just the same, from all that I have heard, from others as well as Peter and you, I’m not sure that the Burroughs Medal is all that important, Certainly not important enough for you to bust a gut and waste a lot of valuable time trying to persuade indecisive people. Or reluctant people. I appreciate everything you’ve done, but I don’t want you to push any further. Let the damned thing take its course.”

All was quiet until January 26, 1968, when Dean Amadon (1st Vice-President of the Burroughs Association) sent a note to Les Line, confiding, “As regards to the John Burroughs Medal for this year, the judges seem to be so completely divided that I doubt whether they will reach a decision at all. One of the prominent judges has come out in favor of Hal Borland, so I think there is hope for next year, if not this year.”

Line sent Amadon’s note to Borland; Borland responded to Line on February 8:

“. . . .I deeply appreciate all your work, but after hearing from various quarters what the members of the committee said, or didn’t say, I have lost a good deal of respect for the award. I don’t expect to get it, and I certainly won’t be disappointed when the announcement is made. To tell the truth, I was let down when I saw the list of officers and directors of the Association, because there were two people on the list for whom I have little or no respect as naturalists. So lose no sleep, waste no indignation, over the matter.”

The following day, February 9, 1968, Borland received an unexpected note from Dean Amadon:

“It gives me the greatest pleasure to tell you that a committee of The John Burroughs Memorial Association* has unanimously recommended that the Burroughs Medal be awarded to you this year. Particular mention was made of your book Hill Country Harvest, but I am sure that the committee also had in mind your other extensive and valued nature writings.

“I hope that this award will give you as much pleasure as it does us, and that you and Mrs. Borland will be the guests of the Association at our annual meeting and dinner on Monday, April 1.

“The public meeting with the award of the Medal will be at 8 p.m. in the auditorium here at the Museum. One of the Directors of our Association, Mr. Rutherford Platt, will show a film on Spitsbergen following the presentation of the Medal. . . .”

*(The group later shortened their name to The John Burroughs Association).

Borland sent his response to Amadon on the 14th:

“I am indeed pleased as well as surprised by the notification in your letter of February 9, which reached me only yesterday. I feel greatly honored to be chosen to receive the John Burroughs Medal this year. I knew, of course, that I had been nominated, but I had not expected to be named medalist. I considered the nomination an honor. The medal will be an accolade.”

Borland also sent a note to Peter Farb:

“I just got a letter from Dean Amadon saying the committee had unanimously picked Borland for the John Burroughs Medal this year. I am stunned, had thought there wasn’t a snowball’s chance, and didn’t give a damn. I wish there was some way to thank you properly for what you did. That ‘unanimous’ stuff may be routine after the fight is over, but whatever happened someone must have talked tough after you put steel into some of their backs. Something happened, and it wouldn’t have happened if you and Les Line hadn’t done what you did. Understand that I do appreciate it.”

Farb to Borland, 2/16/1968:

“That is great news about the Burroughs Medal. Please don’t thank me. I look at it as rectifying a very bad error in judgment. I’m sure actually that anything any of us did was just to get rid of some old lady’s folklore. By the way, Shirley Miller also went to bat for you. She is a great admirer of yours–and also a friend of Farida Wiley’s. She was horrified when I spoke to her and said she would immediately contact Farida and set her straight. I took the liberty of telling one scientist at the AMNH because he helped me put the screws on Amadon and also got me the list and report on who has power in the organization.”

Wiley contacted Borland on the 20th, giving specifics on the ceremony schedule and asking for “a list of names of people you would like me to send invitations to.” In his Feb. 24 note to Wiley, Borland listed twenty-four names to receive invitations.

Borland picked up his medal on April 1, and sent a report of the event to Farb on the 3rd:

“. . . .The performance at the dinner and the evening meeting of the J.B. Assn. was pretty well disorganized, so I’m not even sure who of my friends did get there, but I did see and talk to Les Line and his wife and a few others . . . .My acceptance was no more than five minutes and pretty much the expected, though I did get in a bit about being told that I wouldn’t get the medal because I didn’t know all the warblers, and admitted it, and had trouble distinguishing among the four or five variations on Joe Pye weed. All in fun, of course, ha, ha, ha. But they were very nice, and Farida was charming! . . .But believe me, Farida runs that show, just as you said. Thanks again for all you did. The medal, I am sure, won’t make the slightest difference in what I write or how I write it, but it gives me a certain satisfaction.”

And Borland could not resist a jab at Rutherford Platt in an April 17, 1968 letter to Les Line:

“It was grand seeing you and Lois at the Burroughs Party. You both looked wonderful. I must say I never saw a more thoroughly disorganized event, but the net result was all right–we got the medal! . . .I did get a pretty good nap during Platt’s movie. I tried watching for a bit, but it made me deathly sick, with the combined motion of camera and subject; so I gave up and slept, or tried to, when the sound track eased off. I always did abominate amateur movies.”

Les Line served as Audubon editor until 1991, vastly improving the magazine’s photographic color and reproduction, and publishing perceptive articles on environmental and conservation issues. Under Line’s leadership, Audubon membership blossomed from 35,000 to 500,000; The New York Times declared Audubon “the most beautiful magazine in the world.” Line passed away on May 23, 2010, at age 74. Peter Farb published nearly twenty books on natural history, linguistics and Native Americans, including the classic Face of North America: The Natural History of a Continent. Farb passed away from leukemia on April 8, 1980. He was only fifty.

Farida Wiley led her final bird walk in the spring of 1980, after a fall on Columbus Avenue injured her knee and forced her to leave the New York tradition. She continued on at the Museum for another year, overseeing mailing lists and Burroughs Association affairs, as well as writing book reviews for Natural History and Audubon magazines. Catherine Pessino, Wiley’s longtime friend at AMNH, said, “She was old school, she wouldn’t even make a personal phone call from the office.” Farida never called in sick. She never had a driver’s license. Malcolm Arth, an AMNH director of education, said, “There was something that radiated out of her, a kind of honesty. . . .She confronted you with the kind of directness that is rare in social discourse. There was no phoniness, no subterfuge, no using of people. She was herself. You came away thinking, ‘Now there’s a person.’ “

Her knee gradually worsened and Farida spent her last year at a nursing home in Melbourne, Florida, where she passed away on Saturday November 15, 1986, at the age of 99. In a lengthy obituary, The Washington Post wrote, “Miss Wiley taught people to make a connection with the world, to look up, and out, beyond themselves. . . .She had led an extraordinary life, and was a woman of uncommon character, a product of the 19th century who seemed to have drawn her identity not from movies and magazines but from a clear sense of purpose, her calling as a teacher.” More than 200 people attended her memorial service at AMNH in New York. Friends and co-workers joined scores of bird-walk veterans to share their memories of Miss Wiley:

“I remember one time we saw five warblers under the Pin Oak.”

“Miss Wiley knew birds, plants, animals, trees. I remember finally learning what a Hackberry tree was after 25 years.”

“If there were no birds she knew the flowers, and if there were no flowers she knew the plants and the weeds and the trees and the grasses and the mushrooms.”

“If she’d seen an owl, she wouldn’t want to tell the general public.”

“Everybody felt the same way about her all over the country. Every place I go, anybody who knew about birds knew about her. Everybody called her Miss Wiley.”

“She’d say, ‘If you’re going to talk, you’re not going to hear the birds.’ Heaven help you if you took a leaf off a tree.”

“I was talking to somebody once. That was unforgivable to her. I remember her once–she’d found a little bug, and all these people, lawyers and doctors, were all bent over looking at it, like they were back in school.”

Wiley’s niece, Katherine Feller, remembered listening to Aunt Farida play the piano many years before, her fingernails clicking on the keys as she played. According to Feller, “I think there was a man in her life once.”

Miss Wiley was a spirit that never dimmed. After her passing, her friend Marilyn Godsberg recalled, “When Farida was lonely at the end, she’d get dressed and try to walk to the end of the block.”

Copyright 2022 Kevin Godburn All Rights Reserved

Discover more from halborlandamericancountryman.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.