At 7:55 on the morning of December 7, 1941, Japanese horizontal and dive bombers, torpedo planes and fighters began their surprise attack against the United States Navy Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor, and Army, Air Force and Navy airfields on Oahu, Hawaii. According to military records, 2403 Americans died in the attack, including 68 civilians, with another 1178 injured. Of the 96 vessels in the Harbor on December 7, the battleships Arizona and Oklahoma, and destroyers Cassin and Downes were destroyed; another fourteen ships were heavily damaged but were later repaired and returned to service. On the air bases of Oahu 347 planes were hit, including 188 lost beyond repair. At the time of the attack, the United States and Japan were in negotiations to preserve peace in the Pacific, making the aggression all the more shocking and unforgiveable to the American public, military and government. At half past noon on December 8, President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressed the nation by radio before a joint session of Congress, asking for a declaration of war against the Empire of Japan, which Congress approved soon after.

In the weeks following Pearl Harbor Roosevelt met with Army and Naval commanders, including General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold, Chief of Staff of the Army Air Forces. Roosevelt repeatedly expressed his desire for a retaliatory strike against Japan as quickly as possible. Roosevelt believed that a bombing raid on Japan would restore American morale and shatter Japan’s sense of invincibility. Such a raid would require a joint Naval and Air Force effort. Army bombers would have to be transported to striking distance of Japan by a Navy aircraft carrier, then launched from the carrier deck, something that had never been done before. It was not certain that fully loaded bomber aircraft could fit in the narrow runway space of a carrier, or become airborne in 500 feet or less. And landing the airplanes on a carrier was impossible due to the limited space. After the raid was accomplished, where could the bombers go? In late January of 1942, Naval air operations officer Captain Donald B. Duncan was assigned to oversee the Navy’s role in the raid. To solve the many obstacles facing the Army Air Corps, Hap Arnold called upon a longtime friend, Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle.

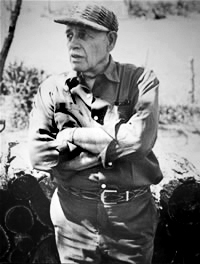

James Harold Doolittle was born in Alameda, California on December 14, 1896. In 1912, after reading an article in Popular Mechanics magazine titled “How to Make a Glider,” Doolittle built his own glider airplane only to destroy it on his first attempt at flight. Doolittle left college in 1917 and joined the U.S. Army Air Service, hoping to become a pilot and see active duty in World War I. He graduated flight school on March 5, 1918 as a second lieutenant, but spent the remaining months of the war as a flight instructor stationed in San Diego. Doolittle continued as an Army instructor into the 1920s, earning a reputation as a talented and innovative pilot, always eager to test the limits of an airplane.

Air shows and air races became more frequent in the 1920s, and Doolittle often flew aerobatic routines at shows, including original stunts he had developed. As airplane designs improved, competition increased between pilots to set new records, to be the “first.” In early September of 1922, Doolittle became the first pilot to fly coast to coast across the United States in less than 24 hours. In late October 1925, Doolittle won the Schneider Marine Cup, a race for seaplanes. In the spring of 1927, Doolittle became the first pilot to fly the difficult and dangerous outside loop maneuver.

In June of 1925 Doolittle had earned a Doctor of Science degree in aeronautical sciences from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Always interested in improving airplane safety and reliability, Doolittle used his knowledge to improve and design new aircraft navigational instruments. By the end of the 1920s many pilots still relied on visual references for level flight–they had to be able to see the ground and the horizon. Flying into a storm, or at night, often ended in a crash when pilots became disoriented and did not know how to rely on their control panel instruments. During extensive tests with his research team in 1929, eleven additional instruments including a magnetic compass, a directional gyroscope, an artificial horizon, an airspeed indicator and an altimeter, as well as improved radio equipment, were installed in Doolittle’s airplane. On September 24, 1929, a “hood” was placed over Doolittle’s cockpit and he became the first pilot to fly blind by completing a fifteen minute flight and landing safely using instruments only.

In late 1929 Doolittle received a lucrative job offer from the Shell Petroleum Company, but, as a chief test pilot for the Army, Doolittle was hesitant to “miss the opportunity of flying and testing every type of aircraft the Army had or anyone wanted to sell it.” In his autobiography I Could Never Be So Lucky Again he wrote:

“What Shell had in mind for me sounded almost too good to be true. The company had conceived the idea that there was a future for aviation as a means of mass transportation, and decided to get into the business of providing aviation fuel and lubricants in America as it had been doing in Europe. All of the ‘name’ oil companies were hiring well-known pilots at that time to represent their products at air races, by setting records and otherwise getting their respective companies in the news in a favorable way. . . .The offer from the Shell Company was one that I literally couldn’t afford to pass up. Three times the military salary of about $200 a month meant a better life for the Doolittle’s. . . .So my decision was purely economic.”

On February 15, 1930, Doolittle resigned from Army active duty, but accepted a commission as a Major in the U.S. Army Air Corps Reserve. In addition to his salary, Shell purchased a beautiful new Lockheed Vega airplane for Doolittle’s exclusive use. (On May 20-21, 1932, Amelia Earhart flew a Vega solo across the Atlantic Ocean, the first woman to do so).

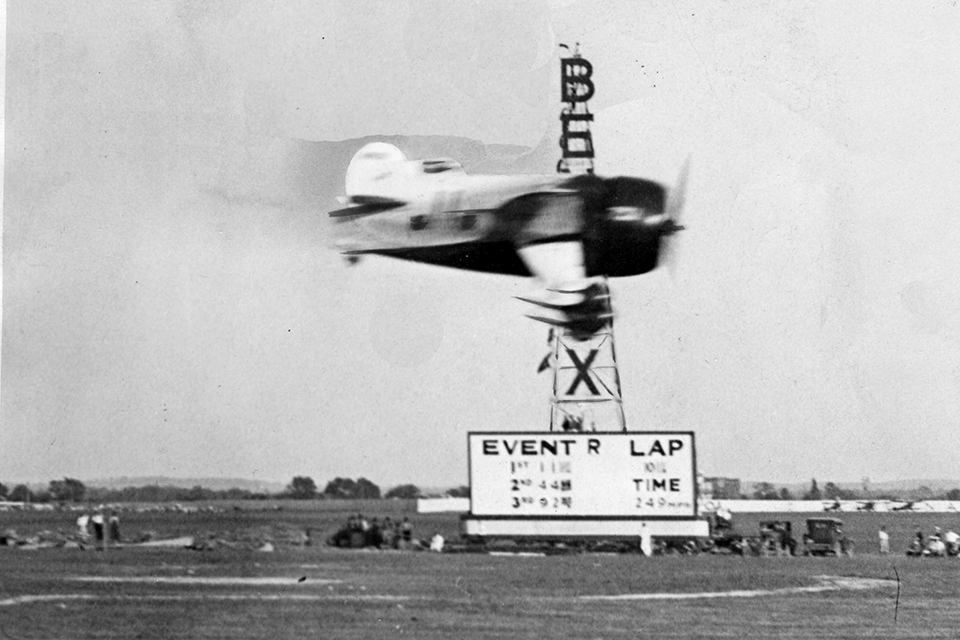

In early September of 1931 Doolittle won the first ever Bendix Trophy cross-country air race, flying a Laird Super Solution biplane from Burbank, California to Cleveland and then on to Newark, New Jersey in a record time of 11 hours and 11 minutes. Doolittle was asked to compete in the September 1932 Thompson Trophy event of the National Air Races in Cleveland flying a Gee Bee Super Sportster R-1, an exceptionally dangerous new airplane designed and built by the Granville Brothers Aircraft Company in Springfield, Massachusetts. In late August 1932 Doolittle flew to Springfield to have a look at the R-1. In I Could Never Be So Lucky Again he recalled:

“The Granvilles had just completed two new models powered by new Pratt & Whitney 750-horsepower Wasp engines, which they designated the R-1 and R-2. . . .It had been flown only once, by Russell Boardman, but he had aborted the flight because the plane was too dangerous. The vertical fin was so small it was virtually nonexistent. There is no doubt the R-1 was a very directionally unstable airplane, despite the fact that the Granvilles had hurriedly added two square feet to the vertical fin and rudder. . . .

“The red and white plane with the 7-11 dice painted on the side was fascinating to look at. Only 18 feet long from prop to tail, it seemed like it was all engine with a miniscule set of wings and a bomb-like fuselage. The extremely small cockpit sat so far back and was faired into the fuselage just in front of the vertical stabilizer. This was no doubt to counterbalance the weight of the heavy engine. The airplane would be difficult to taxi because the cockpit position provided no straight ahead visibility, and with such a small tail area, the wing would also blank out rudder action until the tail was well up on takeoff. On landing, blanking from the wing would probably mean loss of rudder control at a relatively high speed.

“Recognizing that this airplane would be extremely hot to handle, I knew I had to fly it delicately. I walked around it several times to try to predict what it would do in flight. I climbed in, had the hatch closed from the outside, and warmed up the engine. The engine was obviously extremely powerful and ready to go, so I blasted off and headed for Cleveland. I didn’t even make a turn around the field. I could tell from the first moment that it was a touchy and probably unpredictable airplane.

“I made a conservative approach and landed at Cleveland without difficulty, but I didn’t trust this little monster. It was fast, but flying it was like balancing a pencil or an ice cream cone on the tip of your finger. You couldn’t let your hand off the stick for an instant. . . .”

During four qualifying “speed dashes” on September 3, Doolittle set a new world speed record when he averaged 296.287 miles per hour, with one run clocked at 309.040. Later that day as Doolittle started the engine for the race, “the carburetor backfired; flames suddenly engulfed the cowling and started to spread to the rear. I leaped out and a mechanic and I extinguished the fire. . . .I started it up again and taxied out to the starting line.” Doolittle won the race, setting a new record for the Thompson course of 252.686 miles per hour. The Thompson Trophy included a cash prize of $4500; Doolittle was also awarded the Clifford W. Henderson Trophy for fastest qualifying time, and the Lowell R. Bayles Trophy for the world speed record.

Notoriously unpredictable Gee Bee Racers would claim the lives of several pilots in the 1930s, including one of the Granville brothers. After his Thompson win, Doolittle “flew the Gee Bee back to Springfield the next day. I landed it, taxied up to the line, gratefully got out, and thanked the Granvilles. That airplane was the most dangerous airplane I have ever flown. I was asked many years later why I flew it if it was so dangerous, and the only answer I could think of was, ‘Because it was the fastest airplane in the world at the time’. . . .Flying the Gee Bee in that race had a profound effect on my thinking, especially when I learned that a bunch of newspaper photographers had crowded around Jo and the boys waiting to take pictures of the expressions on their faces if I crashed.” Soon after the Thompson win Doolittle retired from pylon air racing.

Doolittle continued to travel for Shell, performing flight demonstrations of new aircraft, and lobbying for more powerful engines and higher octane fuels as well as changes in government policy after observing the United States was lagging far behind European countries in commercial and military aviation. Doolittle was outspoken in his opinions, and since his days as a flight instructor after World War I had developed a reputation as a daredevil, occasionally finding himself fined or his license temporarily suspended for restricted maneuvers. Doolittle also campaigned against closed-course pylon racing after a series of fatal crashes, but “was not opposed to racing point to point against the clock in passenger and cargo planes;” flying coast to coast in record time for example. In mid-January of 1935, Doolittle did just that by becoming the first pilot to fly from California to New York in less than twelve hours with passengers, one of whom was his wife Josephine.

In mid-August of 1939 Doolittle returned from a tour of Germany, where he had observed the superior Nazi Luftwaffe air forces. Certain that “war was inevitable, that the United States would be involved in hostilities,” Doolittle met with Army Air Corps chief Hap Arnold and offered to leave Shell and return to the service full time. Doolittle had known Arnold since 1918 when Arnold was his commanding officer at the end of World War I. On September 1, Germany invaded Poland–the beginning of World War II. By May of 1940 allied forces in Europe were being overrun by Nazi Germany. President Roosevelt addressed Congress, asking for drastic increases in US defenses and production of airplanes. On July 1, 1940, Doolittle, at age 43, was recalled to active duty by Arnold. In November Major Doolittle,

“was transferred to Detroit as assistant district supervisor and designated Air Corps factory representative at the Ford plant. . . .The job as I saw it was to effect a shotgun marriage between the aircraft industry and the automotive industry. Neither one wanted to get married, but it was necessary in order to meet President Roosevelt’s requirement of 50,000 planes a year. Mass production methods for aircraft had to be found and new perspectives adopted. . . .The aircraft industry thought that if they gave all their know-how to the automotive industry, then when the war ended, they would have developed a new and stronger competitor. The automotive industry felt that in building airplanes they would be doing something that they didn’t know how to do, didn’t want to do, and therefore preferred not to. . . .In time, both industries operated in good faith. . . .In retrospect, the automobile industry eventually did a splendid job building aircraft as well as guns, tanks, and other munitions of war.”

On December 8, 1941, the day after Pearl Harbor, Doolittle delivered a letter to his superiors asking to be transferred to a combat unit. The request was not approved, and Doolittle returned to Detroit until January 2, 1942, when Hap Arnold approved Doolittle’s promotion to Lieutenant Colonel and recalled him to Washington.

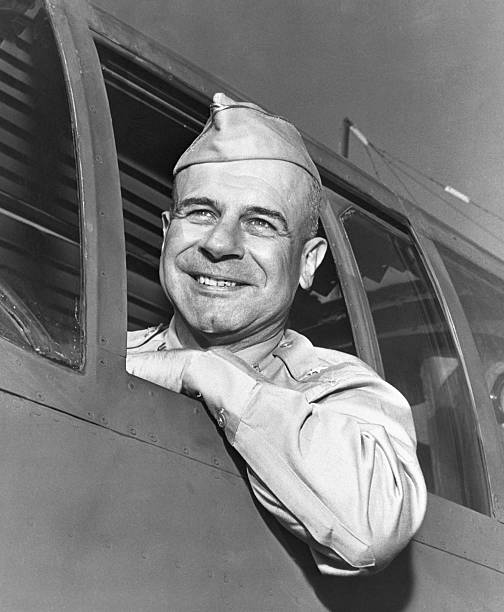

In late January Arnold told Doolittle of the plan for a raid on Tokyo in early April, and placed him in charge of the Air Corps role in the raid. The Navy had designated the carrier Hornet as best suited to transport Army bomber aircraft, and Doolittle quickly determined that the North American B-25 was the only bomber that could operate in the limited space of an aircraft carrier. On February 1, two B-25s were hoisted onto the Hornet at Norfolk, Virginia for a trial run. The carrier steamed to sea; the bombers flew from the deck with ease and room to spare, then returned to Norfolk. But these airplanes were not carrying four 500 pound bombs or extra fuel; it was still not certain that fully loaded B-25s could be safely launched from a carrier.

Doolittle designed modifications for the 24 B-25s under his command, including additional fuel tanks, extension bomb shackles, improved armament and bomb racks, and the installation of 16mm cameras in several planes. In early March the airplanes and volunteer five-man crews arrived at Eglin Filed in Florida and began training on short field takeoffs, machine gun operations and low level bombing. Although Doolittle was in charge of planning the mission, he was not scheduled to fly in the raid. In mid-March Doolittle flew to Washington and convinced Arnold to let him pilot the lead B-25 on the Tokyo raid. In late March the B-25s flew to California for final maintenance and loading onto the Hornet on April 1. Ultimately, only sixteen B-25s would be hoisted onto the carrier. At 8:20a.m. on April 18, 1942, approximately 650 miles from the coast of Japan, Doolittle successfully departed the Hornet, followed by his fifteen B-25s and crews. The Raiders bombed industrial and military targets, then, unable to return to the Hornet, flew on to China. Upon his return to Washington on May 18, 1942, Doolittle was met by Hap Arnold. Arnold told Doolittle they were due at the White House and President Roosevelt was to award Doolittle the Medal of Honor for leading the Tokyo Raid. Doolittle protested, saying; “General, that award should be reserved for those who risk their lives trying to save someone else. Every man on our mission took the same risk I did. I don’t think I’m entitled to the Medal of Honor.” In I Could Never Be So Lucky Again Doolittle wrote;

“The President pinned the medal on my shirt and asked me to tell him about the raid, which I did. . . .He said our raid on Japan had had the precise favorable effect on American morale that he had hoped for. . . .On the way through the door Hap congratulated me. I couldn’t resist telling him that while I was grateful, I would spend the rest of my life trying to earn it. I felt then and always will that I accepted the award on behalf of all the boys who were with me on the raid.”

At the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Hal Borland was a feature writer for The New York Times Magazine, as well as contributing freelance work to several other popular magazines. On one of his assignments for the Times Borland met Jimmy Doolittle, an experience he recalled in a 1962 article written for a Columbia School of Journalism Anniversary Book, to coincide with Borland receiving the 1962 Columbia Journalism Alumni Award. Borland wrote:

“In the early Spring of 1941 I was sent to Detroit to round up a story for The New York Times Magazine on what the automotive industry was doing in the big drive to equip our armed forces for the desperate World War II campaigns then shaping up. In the three months since Pearl Harbor I had been shuttling from one defense area to another, writing about tanks, planes, machine guns, land mines, artillery shells. Now I was to tie up the Detroit story in one tight package.

“I checked in, laid my lines and went to work, in the face of the most confusing and whimsical censorship I had struck anywhere. The automotive people were cooperative, but the censors seemed to be playing games, not only with me but with each other. I ran down and inspected a brand new anti-aircraft weapon before my censor-guide learned that it was top secret. But he told me of a new, super-fast method of rifling machine gun barrels in another plant. I ran it down, got the details, only to have the censor there wash it out for me and suggest that I look in on a brand new tank factory. I got into the tank plant, going full blast while workmen were still finishing the roof, and watched the first tank assembly line in action, only to have that one scratched too by a hot-stuff censor. I played this game almost a week, finally decided to take what I had, go back to New York, write my story and let the office fight it through Washington for clearance.

“I went back to my hotel, packed to leave that afternoon, and went down to the dining room to have lunch. I had almost finished when an eager-beaver censor who had harried me two days before saw me and came to my table. We had coffee together and he asked how things had gone. I told him, frankly. He laughed. Then he asked, ‘You know Jimmy Doolittle?’

“I said no, I’d never met Doolittle.

” ‘I hear he’s in town.’

” ‘Doing what?’

” ‘Oh, this and that.’ Obviously he didn’t know, but he was playing the same old game I had been caught in all week.

” ‘You know where he is?’ I asked. ‘Or is that hush-hush too?’

” ‘Absolutely.’ He finished his coffee and was about to go when he asked, ‘Been out to the old Graham-Paige plant?’

” ‘I hear it’s empty.’

” ‘Practically empty,’ he said, and added, ‘Good luck with your story.’ Then he left me.

“A few minutes later I took a cab out to the old Graham-Paige place. On the way out I tried to piece the Doolittle story together in my memory. Jimmy Doolittle was one of the best airplane pilots of the era, held a whole slew of speed records and had done a good deal of research in aviation fuel for a big oil company. An outspoken man and a top engineer–he held a doctor’s degree in aviation engineering from M.I.T.–he had been so critical of Air Corps policy that he had been commissioned an active major the previous Summer and thus, it was said, muzzled on top-level orders. He was definitely in the doghouse, had dropped out of the headlines and recently dropped out of sight. I wasn’t in Detroit to interview Major James H. Doolittle, but the chance to do so wasn’t one to pass up.

“The Graham-Paige plant was a huge barn of a place and looked deserted. There wasn’t a guard in sight when I walked in. On the huge main floor were sections of a big bomber, roughly grouped in units, and in a far corner, dwarfed by the huge room itself, stood a B-25. I noticed chalk marks here and there on the floor, which looked as big as an airplane carrier’s deck.

“I found a stairway, climbed it to a long corridor of offices in the second-floor wing. I went down the line of offices, all vacant, dusty and cobwebbed. Then I heard a tap-tap-tap at the far end, came to an open office door and saw a girl at a typewriter. She stood up, surprised, and I asked, ‘Where will I find Major Doolittle?’ Maybe I took her off guard. Anyway, she said, ‘The second door down, the corner office.’

“I left before she could ask questions, went to the second door and knocked. A voice inside growled, ‘Come in.’ I went in and saw a stocky man in a brown tweed suit sitting at a battered desk, all alone in the big office. There wasn’t a rug or a drapery or a map or picture on the wall, nothing but that desk, a straight-backed chair, one small bookcase jammed with books, and the man with a rather sharp nose, a broad jaw, a straight-across mouth, a high brow and close-cropped hair. He was scowling. ‘Who are you?’ he asked sharply.

“I told him my name, said I was from The Times.

” ‘I haven’t got a thing to say,’ he said. ‘And even that’s off the record.’

” ‘You can’t even say why you are here?’

” ‘I’m here on orders,’ he said. Then, with a faint smile, ‘That’s off the record too. Right now, I don’t even exist. Understand?’

” ‘All right,’ I said, ‘you don’t even exist. According to the censors, Detroit doesn’t exist either. They want me to say Detroit is working like hell, winning the war, but not making a plane or a gun or a tank!’

“He smiled at my outburst, then asked, ‘What have you seen?’

“I told him. He listened, nodding from time to time. ‘I haven’t even seen some of that stuff,’ he said. ‘And I’m supposed to be doing a procurement job.’ He got up, walked about the room, a caged man, looked out the grimy window and said, ‘I’ve got a lot of time to think, though.’ Then he turned back to me and asked, ‘You’re not a pilot? Or an engineer?’

” ‘No.’

“He came back and sat on the edge of his desk and talked for fifteen minutes. Mostly about planes, bombers, about load capacity, range, air speed, point of no return. I wasn’t sure what he was talking about but I tried to take mental notes. Finally he said, ‘You’ve got your Detroit story. If you clear it through Washington they may go easy on it. But just remember, I’m not here. I don’t exist.’

” ‘One of these days,’ I said, ‘when they take the wraps off, can I have an interview with you? One I can use?’

” ‘See me a year from today,’ he said, ‘and I’ll talk. For publication.’

“I thanked him, we shook hands and I went back down that long, deserted corridor, down the stairway, through the huge room with the bomber components, and out onto the street. Back at the hotel, out of long habit I made notes of all I could remember that Major Doolittle had said. Then I caught the plane to New York.

“In the office the next morning I reported to Walter Hayward, Assistant Sunday Editor. We discussed the story and he agreed that I should write it at my own discretion and we would see how much Washington would pass. Finally I mentioned that I had seen Jimmy Doolittle out there but couldn’t even mention his name. Walter nodded. ‘They’d probably kill your whole story if you did. They’re very touchy about Doolittle.’

“I went back to my desk. Russell Owen, whose desk was next to mine, had just come in. He asked about the Detroit trip and we damned all censors in unison. Then I said, ‘I saw Jimmy Doolittle out there.’

” ‘So that’s where they’ve hidden him,’ Russell said. Then he asked, with a grin, ‘I suppose you interviewed him?’

” ‘As a matter of fact, I did. But it’s all off the record.’

” ‘What did he say?’

“I found my notes. Russell read them, frowning. He handed them back and said, ‘Either he’s nuts or you are. He didn’t say a damn thing.’ I tore up the notes, started to throw them into the waste basket, then took them to the wash room and flushed them down a toilet.

“I wrote my Detroit story and the Washington censors hardly touched it. It was used as the lead piece in the Magazine for March 30, 1941. Then I went to Fort Monmouth, to Hartford, to Pittsburgh, still covering the war industry circuit. From time to time Russell Owen kidded me, asked, ‘Seen Jimmy Doolittle lately?’ My answer was always the same, ‘Next March.’ It was our private joke.

“March came and passed. Then in April came the word. On April 18, 1942, Lieutenant Colonel James H. Doolittle led a flight of sixteen B-25 bombers off the deck of the aircraft carrier Hornet and flew almost 700 miles to bomb Tokyo, Nagoya and Kobe. Mission accomplished and the planes beyond the point of no return, they flew on into China. It was a spectacular, historic feat, the first time bombers had flown from a carrier. Doolittle was credited with planning it and carrying it out successfully.

“The morning we had word of that sensational strike, Russell Owen came over to me the moment he arrived at the office. He held out his hand in silence. Then we both grinned. ‘And just to think,’ he said deadpan, ‘you had that story all that time.’

” ‘All but the date,’ I said. ‘He was a month late.’ It actually was a year and one month, to the day, after I saw Jimmy Doolittle in the old Graham-Paige plant in Detroit.

“For a long time, in my mellow moments, I told myself that I did have that story a year in advance. But in the candid intervals I admitted the truth. I haven’t the remotest idea what was in those notes, but I’ll lay prohibitive odds that they didn’t even have a hint of that story. It was just one of those coincidences that lie warm in the memory.”

It is a terrific story for sure, but one that cannot possibly be accurate. Borland begins the article by saying, “In the early spring of 1941 I was sent to Detroit to round up a story for The New York Times Magazine on what the automotive industry was doing in the big drive to equip our armed forces. . . .In the three months since Pearl Harbor I had been shuttling from one defense area to another. . . .Now I was to tie up the Detroit story in one tight package.” This, of course, is impossible. Pearl Harbor did not happen until December 7, 1941, more than eight months after Borland was sent to Detroit. Three months after Pearl Harbor would have been March of 1942. The obvious question is maybe this was simply a typo, an honest mistake. In my research on Borland I have seen instances where he did occasionally confuse dates. But I quickly found that this was not a typo. Borland’s Detroit story, titled “Machine Shop for a War of Machines,” appeared in The New York Times Magazine on March 30, 1941. Borland also wrote that the Tokyo Raid “actually was a year and one month, to the day, after I saw Jimmy Doolittle,” which means that Borland met Doolittle on March 18, 1941, months before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

Doolittle was stationed in Detroit from November of 1940 until Hap Arnold recalled him to Washington on January 2, 1942. It seems likely that Borland and Doolittle did in fact meet in March of 1941. But what would their conversation have been? Borland’s recollections of seeing a B-25 and chalk marks the size of an aircraft carrier, of Doolittle talking about “bombers, about load capacity, range, air speed, point of no return,” and “see me a year from today, and I’ll talk for publication,” certainly did not happen. Doolittle would not have been conducting any of these tests in March of 1941 because, again, Pearl Harbor and the Tokyo Raid were still months away.

And what can one make of the final paragraph of Borland’s article? He writes that he did not have “the remotest idea what was in those notes,” and “I’ll lay prohibitive odds that they didn’t even have a hint of that story.” Is he saying that the article is fiction? Is he being modest and trying not to take too much credit for his reporting? It is a baffling piece of work. Editors for the Columbia School of Journalism Anniversary Book apparently had doubts as well–they never published it. Borland’s recollections of Doolittle were written in 1962, twenty-one years after their meeting took place. Although his memory and intention in 1962 seem unclear, the article provides an interesting introduction to the impressive body of work that Borland turned in during World War II.

Borland was hired by The New York Times in early March of 1937, after spending eleven years as an editor and book reviewer for Cyrus Curtis-owned newspapers in Philadelphia, home town of his first wife Helen. (Borland also published four books in the 1930s: Valor: The Story of a Dog, Trouble Valley and Halfway to Timberline under the pseudonym “Ward West,” and Wapiti Pete). Borland had hoped to leave the newspaper business the previous year. In a February 6, 1935 letter to his soon-to-be agent, Borland wrote, “I figure on cutting loose from the newspaper job in the spring of 1936 and free-lancing entirely, if at all possible.” Instead, Borland joined the staff of Lester Markel, Sunday Editor for the Times. One of Borland’s earliest nature-themed pieces for the Times originated in memos exchanged between an assistant editor and Markel in November of 1938. An article was proposed on “animals that are left in industrialized America and what they do for a living.” Markel responded, “A rather nice idea this. John Kieran won’t take it on; who might?”. . . .”I learn that Borland is a nature expert. How about trying him?”. . . .”By all means, let’s try Borland.” Among his other early work for the Sunday Times Magazine, Borland contributed lengthy cover features on the 1939 and 1940 World’s Fairs as well as a February 2, 1940 article on the Amish community in Pennsylvania, while his article “Builders Three, My Boys and Me” appeared in Better Homes & Gardens magazine in November of 1940. Borland also began his “About” column for the Times, featuring informational anecdotes on a variety of topics. And Borland continued submitting short stories to magazines, including “Song of a Man,” published in The American Magazine in September 1939. In 1963, Borland would expand this story into his best-selling novel When the Legends Die.

On October 8, 1941, Borland’s short nature piece “Oak For English Hearts” appeared in the Sunday Times. This would be the first of what Borland called his weekly “nature editorials,” 275-word essays that were published at the foot of the Sunday editorial page without a byline but readers knew were written by Borland. Borland continued to write them for the remainder of his life; editorial #1721 ran on December 30, 1973, #1868 in January 1977. His final editorial–over 1900 in all–was published on February 21, 1978, the day before his death. The editorials were immensely popular, with Borland often receiving as many as 3,000 letters a year from readers. Borland typically wrote the essays on Tuesday, revising them several times until he was satisfied he had captured his intent in the compact span of 275 words: “I have two gauges for them–they must read well aloud–on that I am somewhat fanatic; and they must be accurate when they deal with technical matters, absolutely accurate. Beyond that, I try to avoid sentimentality, though I do approve of sentiment and emotion.” But Borland was also well aware that the editorials were only one element of his work. In an August 27, 1956 Author’s Biographical Questionnaire, submitted to his publisher for promotion of his book High, Wide and Lonesome, Borland wrote:

“I’d rather not present myself as a newspaperman or even primarily as an ex-newspaperman. I am not a newspaperman who wrote a book. I’m a writer who once worked for the newspapers. The weekly pieces I do for The Times are a minor part of my work, though I know that they must have a place in presenting this particular book, since they are an approach to a good many readers.”

(Ironically, many readers of Borland know, and knew, him primarily from his Sunday editorials and the three collections of them published in book form: An American Year, Sundial of the Seasons, and Twelve Moons of the Year. I am often surprised at how few Borland fans are aware of his extensive newspaper and magazine work, and are familiar with less than a dozen of his 36 published books).

In response to the attack on Pearl Harbor Borland wrote the long, patriotic poem “America is Americans” for the Sunday Times Magazine. The poem was published on December 21, 1941 and received an immediate and overwhelmingly positive reaction from readers. Over the next few months Borland wrote several more war poems for the Times and The Saturday Evening Post, including “Creed” and “Mission at Legaspi.” Scripted dramatizations of “America is Americans” and “Creed” were performed in 1942. A collection of Borland’s war poetry was published in book form in the fall of 1942 under the title America is Americans. Selections from the book were widely reprinted in anthologies and read at public events throughout the war. Borland recalled that “Creed” was “read over the air on a national network, NBC as I recall, the night Franklin Roosevelt died, as a tribute to him.”

Borland’s article “The Enemy Within,” on the dangers of enemy spies and saboteurs working in U.S. factories, was published in the Times in February of 1942. As his war poetry became popular on radio, Borland found himself in demand for more radio work:

“For a time in the spring of 1942 I was loaned by the Times to the Government to write scripts for the radio program ‘Keep ’em Rolling,’ put on by the Office For Emergency Management, MC’ed by Clifton Fadiman. A thankless job, but a look at radio and its peculiar people. . . .a series of programs of information and entertainment. . . .our entertainment is made up of song and drama dedicated to what we in America are fighting for and why; our information is an effort to answer the question that is uppermost in everyone’s mind these days–‘what can I do to help in this fight?’ “

Programs aired Sunday nights from 10:30 to 11:00. Each program began with the announcer exclaiming “Remember Pearl Harbor!” followed by the sound effect “roar of machinery” going to war, and the announcer pleading “Keep ’em Rolling!”

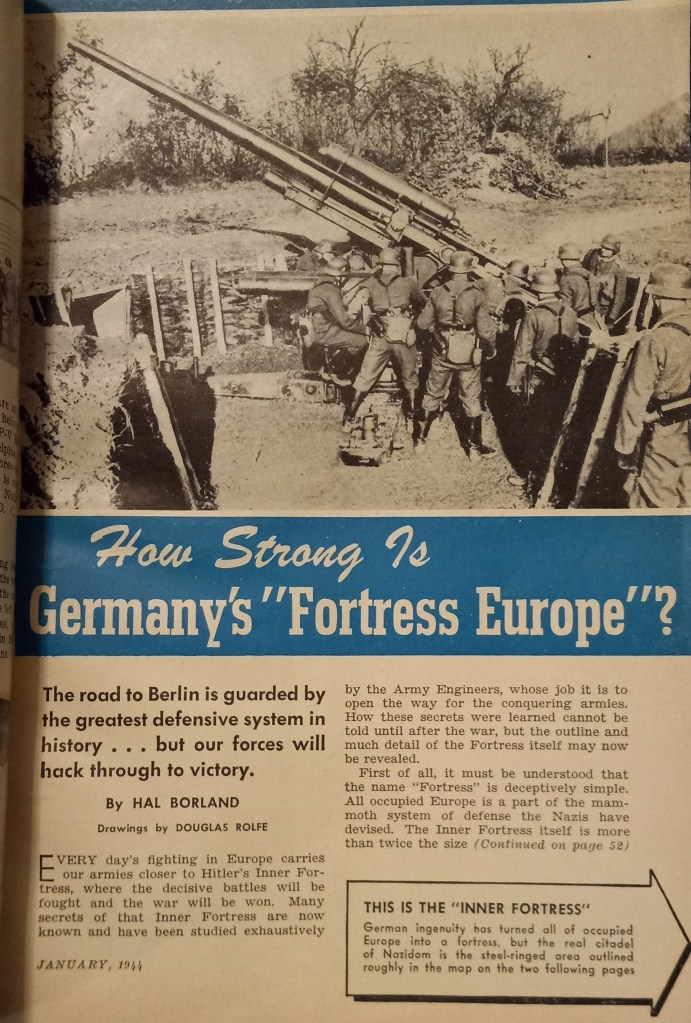

Borland resigned the Times in the summer of 1943 to freelance: “Several magazines wanted me to write for them. I left the Times with the understanding that I would continue on a semi-staff basis, accepting magazine assignments and other work as I pleased. . . .After I left the Times I did correspondence of various kinds for Popular Science Monthly, The Saturday Evening Post, and a dozen other magazines. Quite a bit of work for This Week mag; many others, general reporting as well as essays, usually on some nature phase. A number of pieces for Holiday, several for Reader’s Digest.” In his November 1943 Times article “Home Town Makes Good,” Borland revisited Flagler, Colorado, reporting on the changes made since he lived there in the late teens and early 1920s, and the young men of Flagler serving in the war. The January 1944 issue of Popular Science Monthly featured an in-depth Borland article on the intricate system of Nazi defenses constructed throughout occupied Europe–deadly barriers the allies would have to cross before reaching “Hitler’s Inner Fortress, where the decisive battles will be fought and the war will be won.” Borland also scripted film documentaries on Navajo Indians, nature and geology, and continued writing short fiction, including his story “Beaver,” published in 1944 in the Avon Modern Short Story Monthly alongside stories by Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, Max Brand and Kay Boyle.

Borland endured personal tragedy in the 1940s; his wife Helen died on October 29, 1944 after having brain surgery. During the summer and early fall of 1945, Borland took an extended break from New York and traveled across the country researching an idea he had for an article on the American spirit at the end of World War II. During this trip, Borland and his second wife, also a writer named Barbara Dodge, were married in Denver. The Borland’s returned to his home in Stamford, CT, where he wrote his article, “Sweet Land of Liberty.” It begins; “I have just returned from four months in America. Four months and 12,000 miles, re-examining and renewing contact with the fruitful hills and valleys and plains and valleys, the farmers and tradesmen, the store keepers and school teachers and loggers and factory hands of these United States.” Borland then reports his observations of a country of contrasts:

“I have seen such plenty as no European, no Asiatic ever dreamed of. Ripening corn fields that seem to fill the whole of midland America. A wheat harvest so huge there were not enough granaries and elevators and freight cars to hold it all, and it spilled over in mammoth piles along the railroad sidings. Timber sufficiently to decently house every American and have enough left over to rebuild most of Europe. Steel and copper and aluminum pouring from smelters and blast furnaces and rolling mills in a stream surpassing the combined production of all the rest of the world. . . .Nearly 140,000,000 Americans, men and women at work, producing such plenty as no other land on earth ever knew. . . .And now I have come back to an Atlantic coastland so tense, so full of fears and doubts and wonderings about the future. . . .that it jumps half out of its skin at the touch of an unfamiliar hand or the sound of an unfamiliar voice. . . .Any metropolitan center fancies itself as supersensitive to new trends, new movements, new ideas, and New York likes to believe it is super-supersensitive. But the great bulk of America, and of the American people, lies not only west of the Hudson but west of the Alleghenies. For that matter, go fifty miles from New York in any direction and you begin to feel a wholly different pulse, a pulse much nearer the beat of the American pulse as a whole. . . .The heart of America is sound. The body is strong. The mind is sane, and the eyes are clear.”

“Sweet Land of Liberty” was published in The Saturday Evening Post on December 22, 1945. Nine days later, on December 31, Borland’s youngest son passed away at the age of sixteen. (A heart attack would claim the life of Borland’s oldest son in March of 1963, at the age of 38).

After the war, Borland continued his freelance work and spent a good part of the late 1940s and early 1950s collaborating with Barbara on magazine fiction, a popular genre at the time. It was a productive and joyful period for Borland. In an August 1946 letter to a friend he wrote, “Much has happened since I saw you. After two deaths in my family, I remarried a year ago and we bought a couple of acres up here (Farms Road in Stamford, CT), delightfully rural and ideal for two writers who at last have found that love and happiness are real.” As the fiction market cooled in the mid-50s, Borland turned his full-time attention to writing books; between 1956 and his death in 1978 Borland completed 29 books. But he never fully left the magazine or newspaper business. Borland was a regular contributor to Audubon, Better Homes & Gardens, The Progressive, and American Heritage magazines, among others, wrote as many as 500 book reviews a year for Harpers and The Saturday Review, and for many years wrote weekly columns for The Berkshire Eagle and The Pittsburgh Press newspapers. Not surprising, given that Borland had been a newsman since the age of fifteen when his endlessly talented father taught him the newspaper trade.

Copyright 2025. Kevin Godburn. All Rights Reserved

Discover more from halborlandamericancountryman.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.