Will Borland was not a man to wait for opportunity to come his way. Though less than five foot eight, he was a tough 200 pounds with dark hair and mustache and determined facial features–a rugged and restless son of the American Frontier. Will’s ancestors migrated from Scotland and settled in New York State shortly before the Revolutionary War. After the war, the family moved to the wilderness of western Pennsylvania, then farther west to Hardin County, Ohio, where Will (William Wallace Borland) was born on February 2, 1837. Will’s father and mother eventually packed their small children and few belongings and pushed even further west into Indiana, settling near Lafayette.

When Will was a youngster, he accidentally jabbed the point of his father’s knife into his right eye while whittling. The accident left him blind in that eye as well as scarred, but did not prevent him from becoming an expert left-handed rifle shot. (It also did not stop him, years later, from trying to enlist in the Union Army during the Civil War, though he ultimately was not allowed to serve). Will learned early the necessity, and the rewards, of hard work on the expanding western frontier. The Borland’s cleared and farmed their land, and by his late teens Will was an experienced farmer as well as a highly skilled blacksmith, carpenter and wagon maker. Will set up his own blacksmith shop and quickly established himself as a respected craftsman and successful businessman.

In 1860, twenty-three-year-old Will married Deborah A. Sexton, the eldest daughter of a family from Lafayette, and children followed soon after. Will had inherited his father’s and grandfather’s pioneer spirit, as well as a fearless ability to recognize and seize upon new opportunities. In 1866, inspired by the thriving Homestead Act of 1862, Will and Deborah and their young family joined a wagon train and traveled west across Illinois and Iowa into the Nebraska Territory, filing a claim in Johnson County in the small agricultural community of Vesta, which at the time consisted of only ten families. Will’s father (Will Sr.) and brothers John and Christopher were also part of the wagon train and took homesteads nearby. Will cleared his land and built a home, and for the next six years farmed and raised stock. Children continued to arrive every other year.

By 1872 Will had outgrown the quiet village of Vesta. He sold his claim and moved northwest, filing a claim on a new homestead in the larger town of Sterling on the Nemaha River. Once again he cleared his land and built a home, along with a dam and water wheel to harness the energy of the river. He built a grist mill and forge and opened his blacksmith and carpentry shop. Will became a community leader, joining local civic groups and taking an active role in the development of Sterling. His brother John also moved to Sterling, and contributed by becoming a school teacher and serving as town clerk.

At the time of the move to Sterling the family had grown to six children, two boys and four girls. The oldest were now big enough to take on farming and household chores and help Will in the busy shop, which was often a dangerous place to be. Will was endlessly over-confident in his ability and strength, a fault which led to some careless and painful accidents. Once, while trying to shoe a particularly violent Percheron Stallion, he attempted to hold the horse’s hind hoof between his knees rather than subdue the hostile animal with a twitch–a leather harness attached to a pole that is placed over the horse’s nose then twisted and tightened. Will managed to nail on one shoe, but as he grabbed the other hoof the stallion lunged free and kicked him headfirst into the wall of the shop, which splintered from the impact. An enraged Will jumped up, grabbed a wagon spoke leaning near the door, and knocked the raging stallion to the ground with one blow to the head. Before the dazed animal could recover, Will tacked the remaining shoe onto the trembling hoof.

Will took pride in his shop and tools, which were always perfectly maintained and razor sharp. Will was a master carpenter and craftsman who could build a covered wagon with no drawings to guide him. One day he was cutting away on a slab of hickory hardwood with a short-handled axe, forming a new spoke for a wagon wheel, while his 10-year-old son stood close by. Will expertly worked the axe and wood but had failed to notice a knot in the grain. The axe glanced off the wood and cut deep into his left wrist, nearly amputating the hand. Will quickly grabbed up the severely injured and gushing left hand with his right, holding it tightly against the wrist. As his terrified son looked on, Will cussed and stormed furious out of the shop. He headed toward the doctor’s office two blocks away, taking care to walk in the dirt of the street rather than on the wooden sidewalk because he knew the women of Sterling did not like to pass along a bloody sidewalk. Without the aid of anesthetics, the doctor sewed the severed veins and tendons back together, stitched the hand and wrist, then set the hand with a splint and bandages. After leaving the doctor’s office, Will hurried to the saloon where he hastily downed several shots of whiskey to ease the stabbing pain. When the bartender asked him what was wrong Will roared, “I cut my damn hand off and the doctor just finished sewing it back on!”

Will was back in the shop later that same day, doing what he could with his good hand while his sons helped with the more difficult jobs. The wrist gradually healed, but because of the shortened tendons Will was never again able to fully open the hand. He could open it enough to manage his tools, though, and once fully healed he could lift an anvil with the damaged left hand. Life returned to normal, and his sons began to notice that when work in the shop was slow, Will would busy himself with some small, secretive project that he carefully kept hidden from them whenever they entered the shop.

At age 35, Deborah became pregnant with her seventh child. The hardships of frontier life and births of six children had taken their toll, and she was aged well beyond her years. Though the seventh birth (a daughter) was not unusually difficult, Deborah was physically drained and her recovery was slow. For nearly two months the oldest daughter, Rose, took over the household chores while Deborah remained in bed. Will was shaken by his wife’s poor condition, but gradually she improved and was strong enough to manage the household again.

For the next several months Deborah seemed fine. Then, unexpectedly, early in the winter of 1873, Will came home and found Deborah in bed with what appeared to be a bad cold. She had him soak a rag in turpentine and prepare a mustard plaster for her chest, just as she had done for Will many times before. But they had no effect and she coughed violently throughout the night. By morning, Deborah had an intense fever and knew that her time was short. She called for Will repeatedly during the day, whispering to him, “I did my best, the Lord must understand,” and telling him to “find someone who will be good to the children.” On the second day she called again for Will but did not recognize him when he came, and could not see or feel him holding her hand. She said faintly, “He will hear my voice and come, he always did,” then she quietly died.

The family suffered through the winter, their loss made worse by unusually biting cold and heavy snow, and by the spring of 1874 Will knew he had to act. Leaving Rose to care for the household and his sons to tend the shop, Will set out for Indiana. Within six weeks he was back at the Nebraska homestead with a new wife–Deborah’s youngest sister Angeline. “Anna” was tall and slender with a narrow face and large nose and bitterly sarcastic tongue. She was only 22, far younger than Will and not particularly fond of the outdoors, but she managed to ease into her new role as wife and mother. Her nieces and nephews, who were now her stepchildren as well, seemed to adjust to the change with little difficulty.

Will and Anna would go on to have nine children together. Hal Borland’s father, William Arthur Borland, was the third son of Will and Anna, born on May 13, 1878. All of Will’s sixteen children inherited his determination and willingness to work and lived full and productive lives. When the town of Sterling incorporated on July 8, 1876, Will was among the town’s first elected Board of Trustees. Will continued to run his shop until his death at age 59, on August 25, 1896. Angeline passed away in 1922. After Will died, the boys were going through his desk at the shop and discovered what he had been secretly working on in his spare time for so many years. Inside a cardboard box they found a collection of miniature horseshoes, all the size of a quarter, and each one brightly polished and rendered in perfect detail.

William W. passed away four years before Hal (Harold) Borland’s birth, but Anna and the Clinaberg’s (parents of Harold’s mother) survived into the second and third decades of the 20th-century. In his article “The Plenty of the Land,” published in the November-December 1967 issue of Audubon magazine, Hal Borland paid tribute to his beloved Grandma and Grandpa Clinaberg, and presented two very different portraits of his grandmothers, Borland and Clinaberg:

“There were two grandmothers, but the other one was a widow–starchy, reserved and critical. She distrusted sunlight, which faded her carpets. She insisted nature belonged outdoors, and didn’t think much of it even there. When I visited her I sat on the edge of a chair and silently hated the world. She was Grandmother, capitalized, formal.

“Grandma, on the other hand, was slippery elm bark and cherry-sap gum, dandelion greens and sassafras tea. I think of her every time I smell black walnut hulls; which is one reason we go out every autumn, here in our Connecticut Berkshires, and gather a few pecks of butternuts and hickory nuts, and try to beat the squirrels to a few handfuls of hazelnuts, though we seldom succeed.

“I am sure Grandma was a slapdash housekeeper, and as a cook she fried her meat and boiled the life out of her vegetables. She was a tyrant in many ways, and when she was ‘on the prod’ even the hogs stopped grunting. But she was of the land and partner with it. . . .She was full of frontier skills and old-time lore. . . .a kind of pioneer matriarch who at times seemed to be trying to perpetuate her frontier girlhood in a twentieth-century urban setting.”

In “The Plenty of the Land,” Borland recalled his boyhood visits to the Clinaberg farm in Tecumseh, the skills he learned, and the profound influence they had on his future:

“We usually went to Grandma’s for Thanksgiving, sometimes for Christmas. And every summer I spent at least a week there, sometimes two. Whenever I went, I became a part of Grandma’s work force. Grandpa was the only member of the household who wasn’t a daily part of her crew. He harnessed his horses and was gone right after breakfast and didn’t come back till suppertime.

“Practically everything on that table came from Grandma’s own domain. I had a hand in the growing or harvest of most of them. I helped feed the turkey, helped pick the sage in the stuffing. I picked potato bugs off the vines in the back lot where those creamy mashed potatoes grew, fed bran to brindled Daisy whose milk produced the cream and butter. I kicked over the tops of the onions to make them bulb. . . .I picked apples, shelled walnuts, pressed cider that went into the mincemeat. I picked my full share of the wild strawberries in the jam and the chokecherries in the jelly.

“And that is why we go out and gather a few pecks of nuts every fall–to participate directly in that plenty, to help ourselves. That is why we live on the land.”

And in a previously unpublished family remembrance, Borland described Will and Anna:

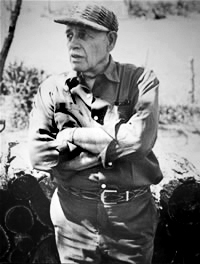

“There was Grandfather Borland, whom I remember only from a framed photographic enlargement that once hung on a wall, the picture of a stern man with dark hair and a firm chin and an ample nose and a dark mustache, not huge but ample. . . .He was short and stocky, a tough thewed man.”

“She hadn’t been overly endowed to start with, for she was the tall, stringy type, as she said, with a long, bony face and a long nose. She had looked thirty when she was 22, and she looked 35 now that she was 40. She never, to the end of her days, looked a day over 45, and she lived to be almost eighty.”

Copyright 2014 Kevin Godburn All Rights Reserved

Discover more from halborlandamericancountryman.com

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.